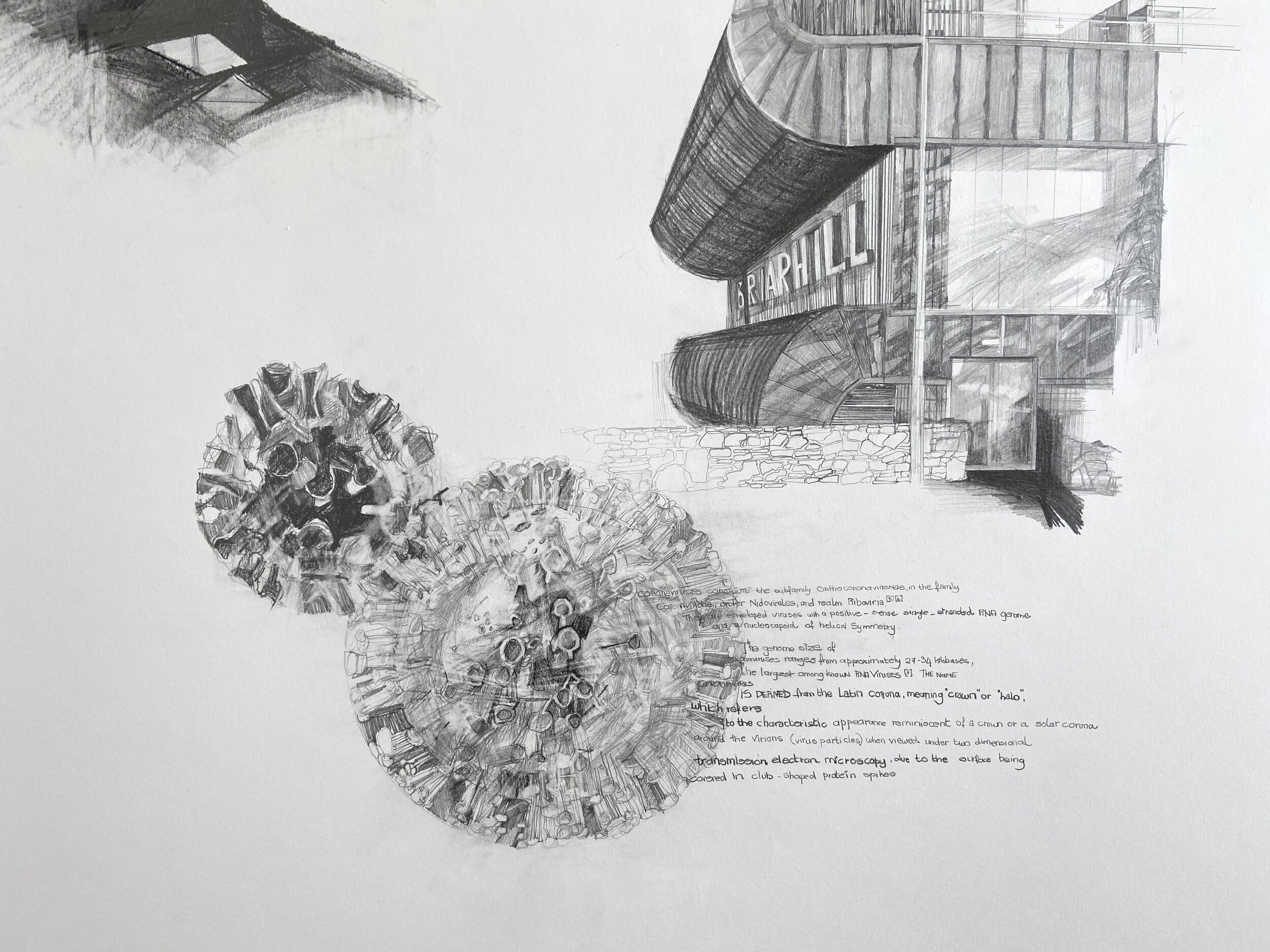

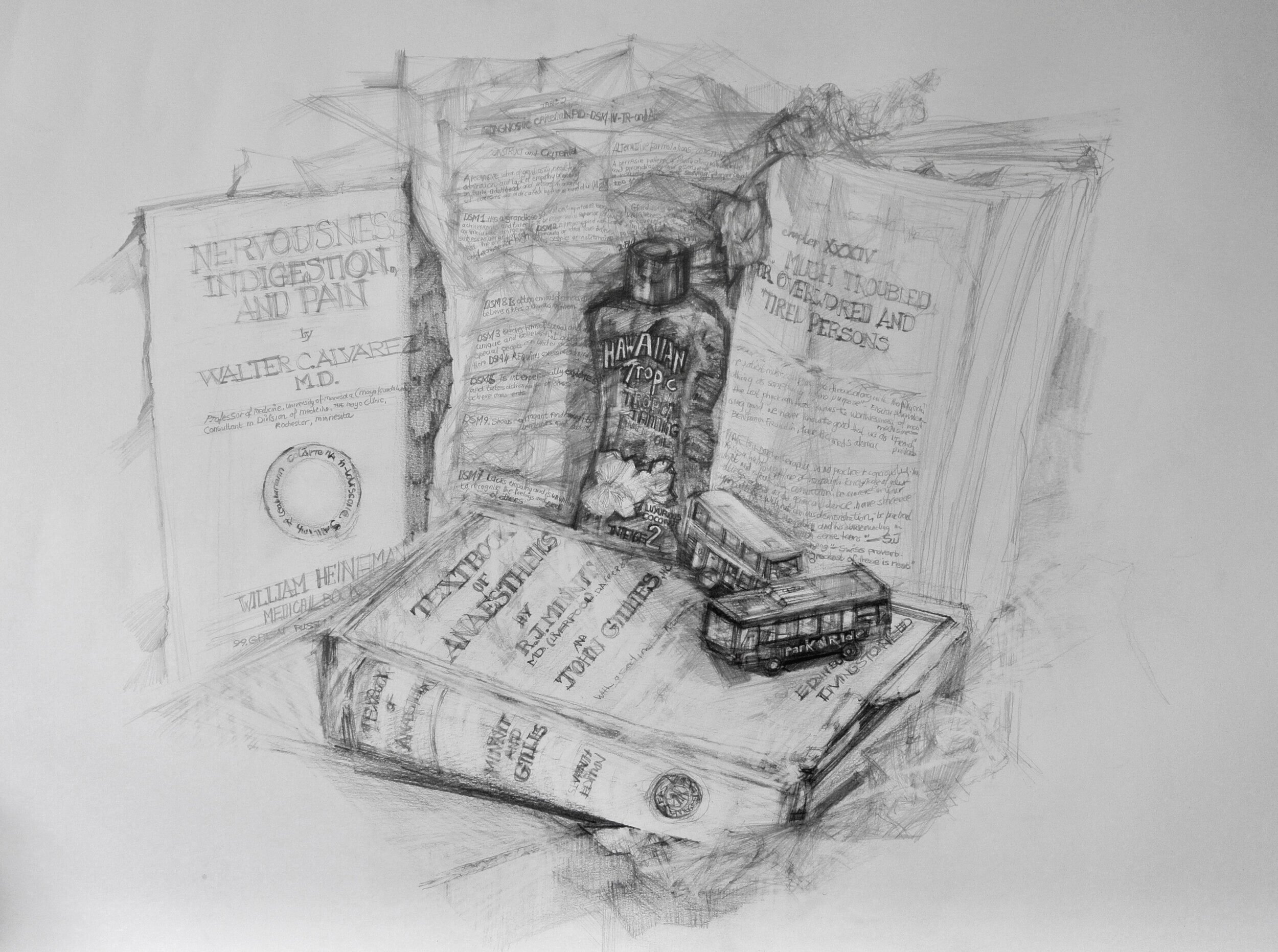

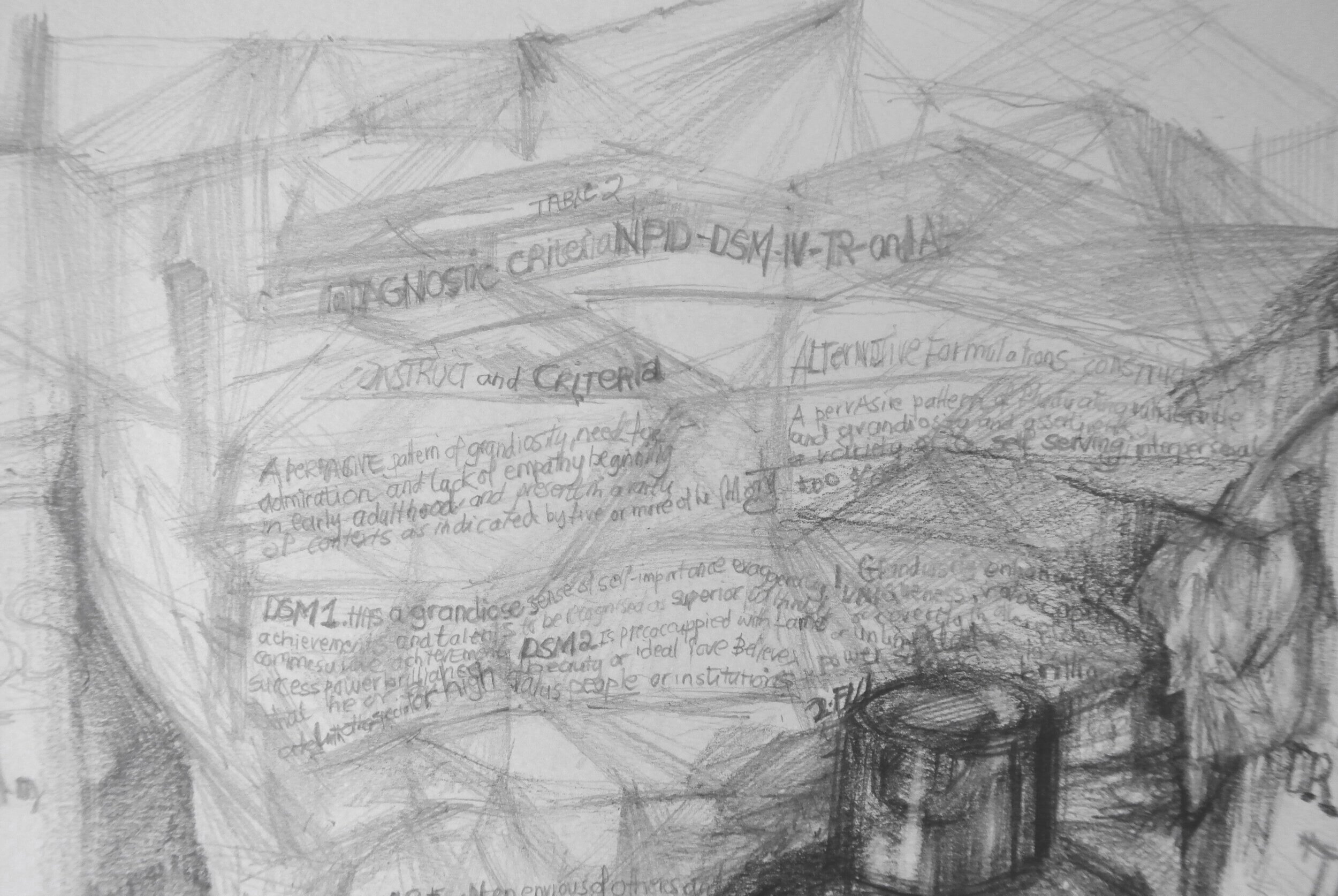

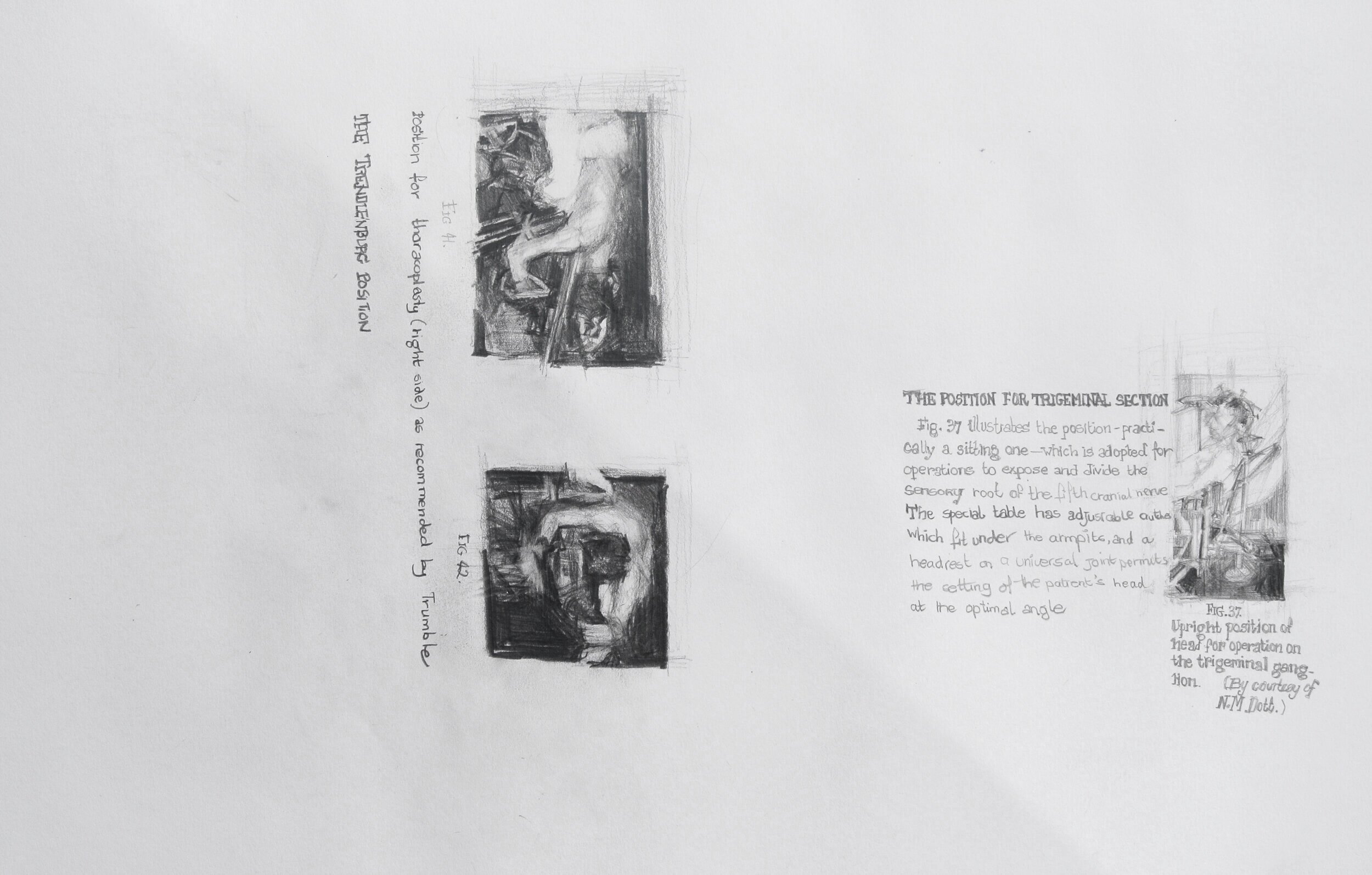

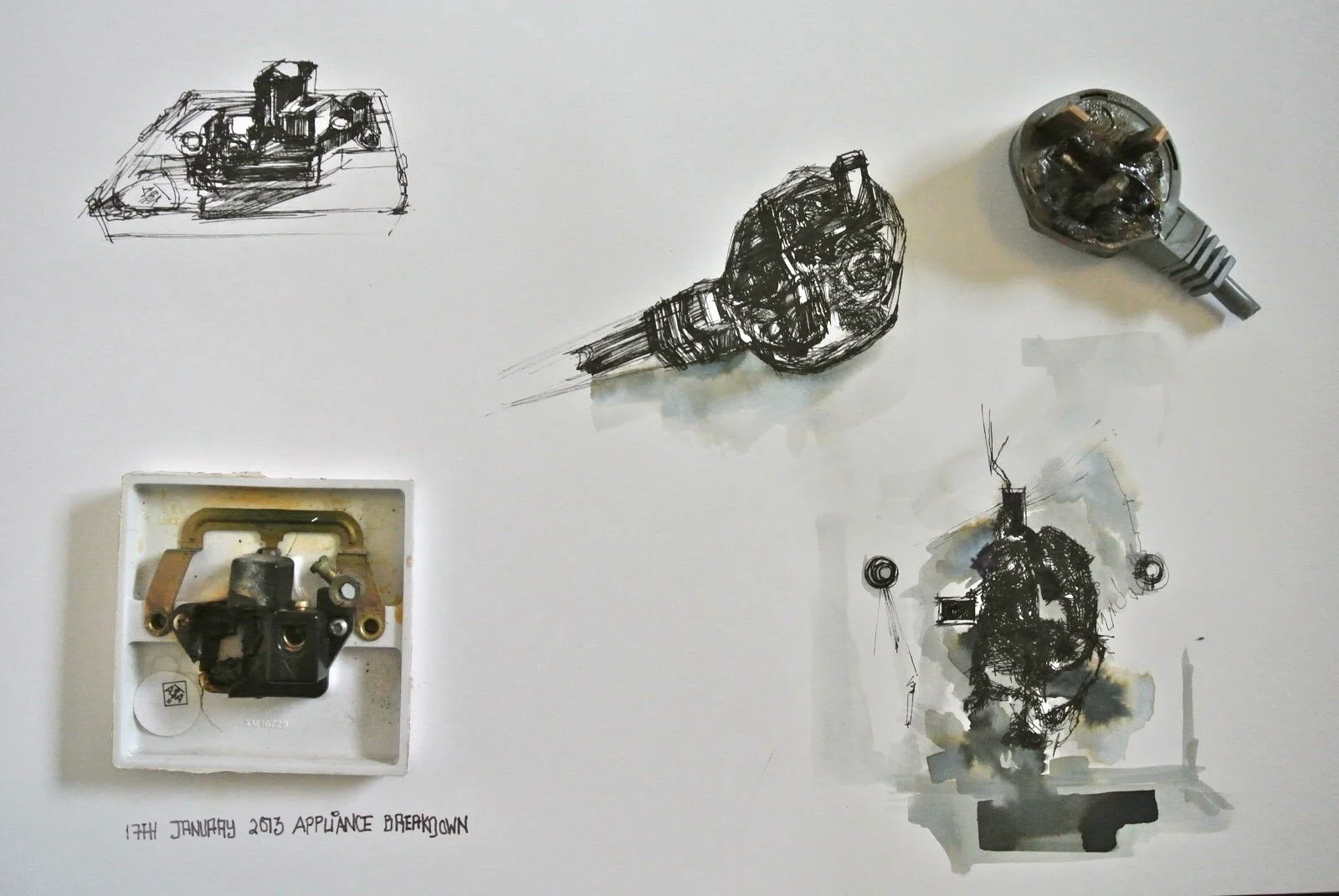

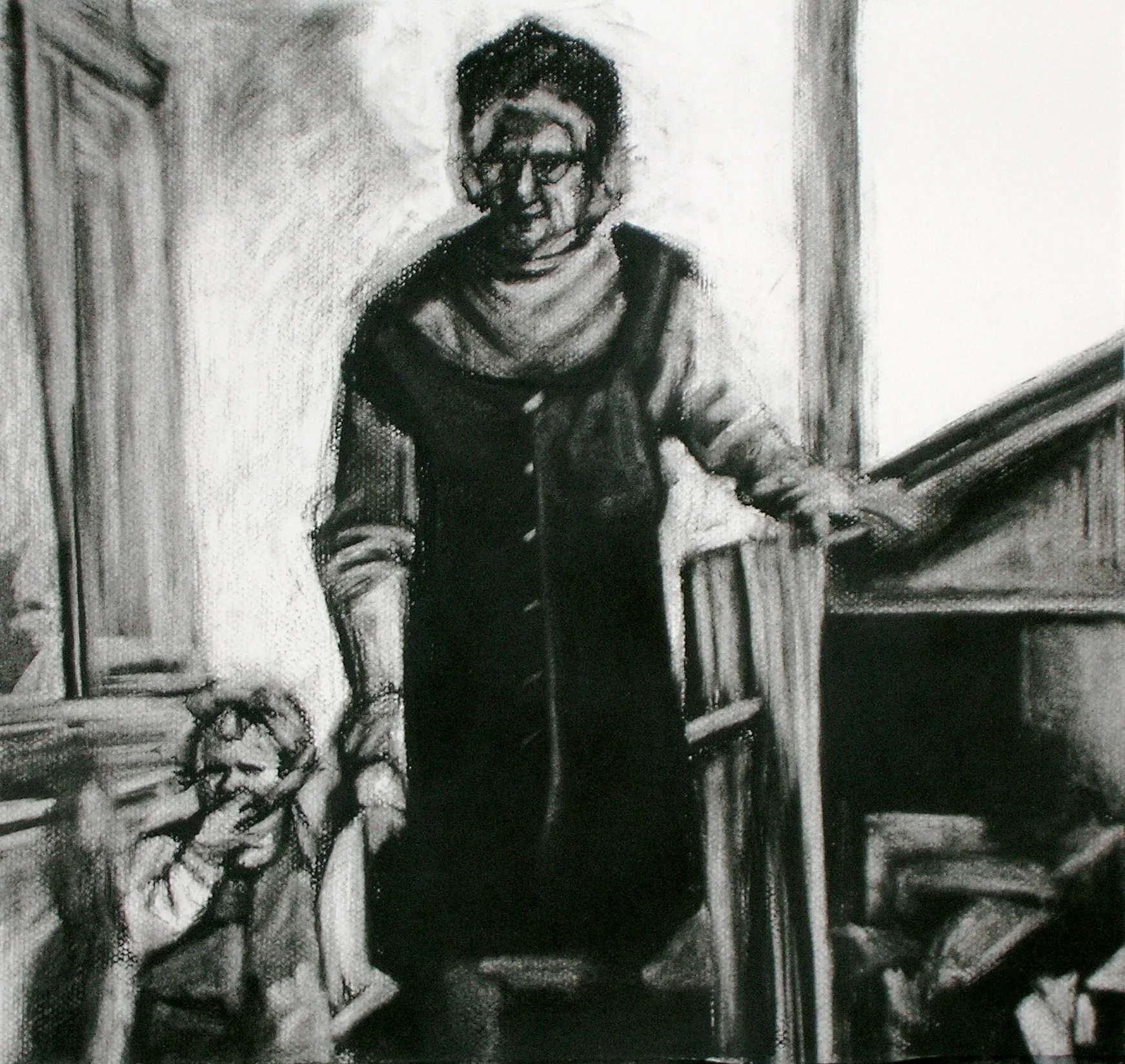

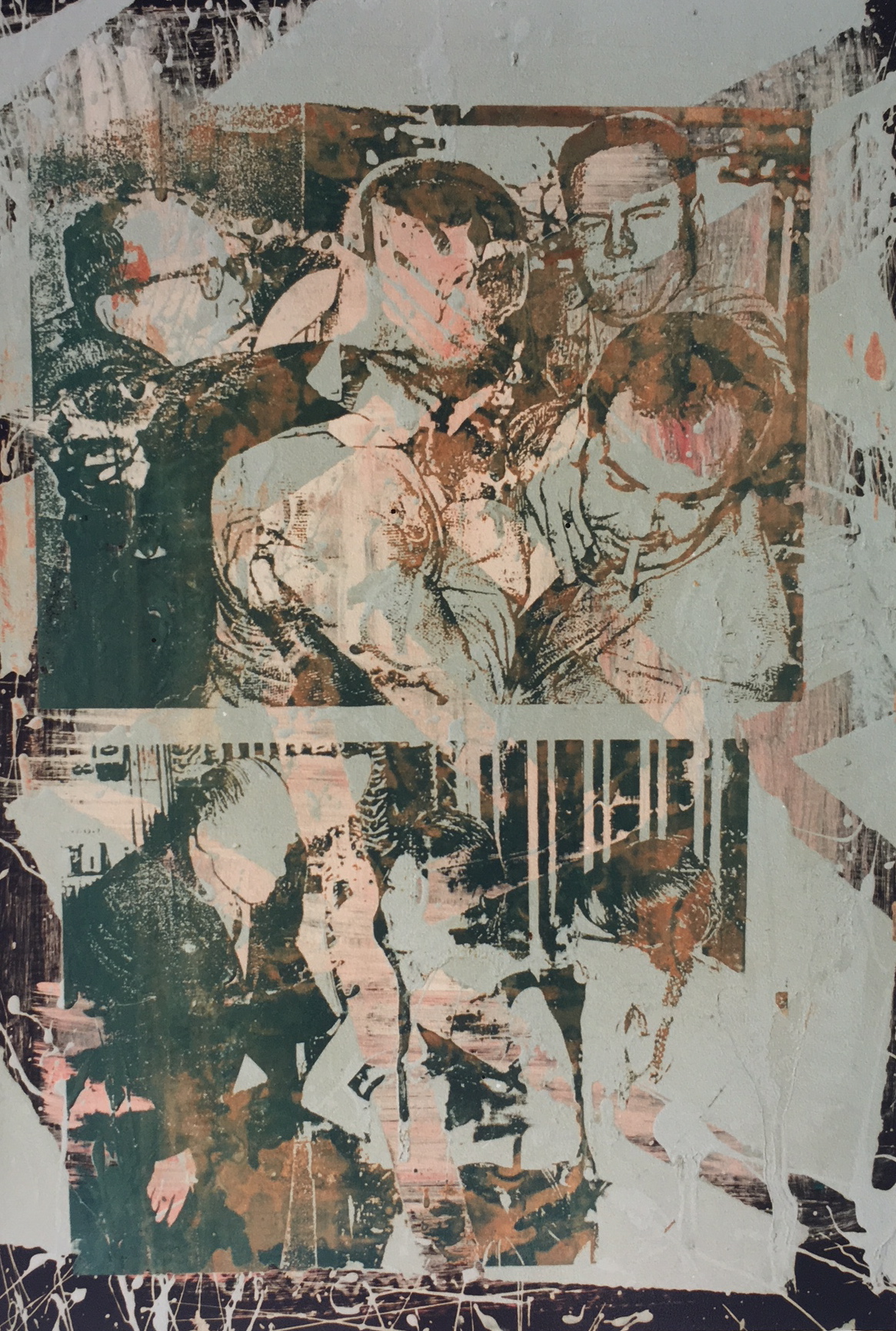

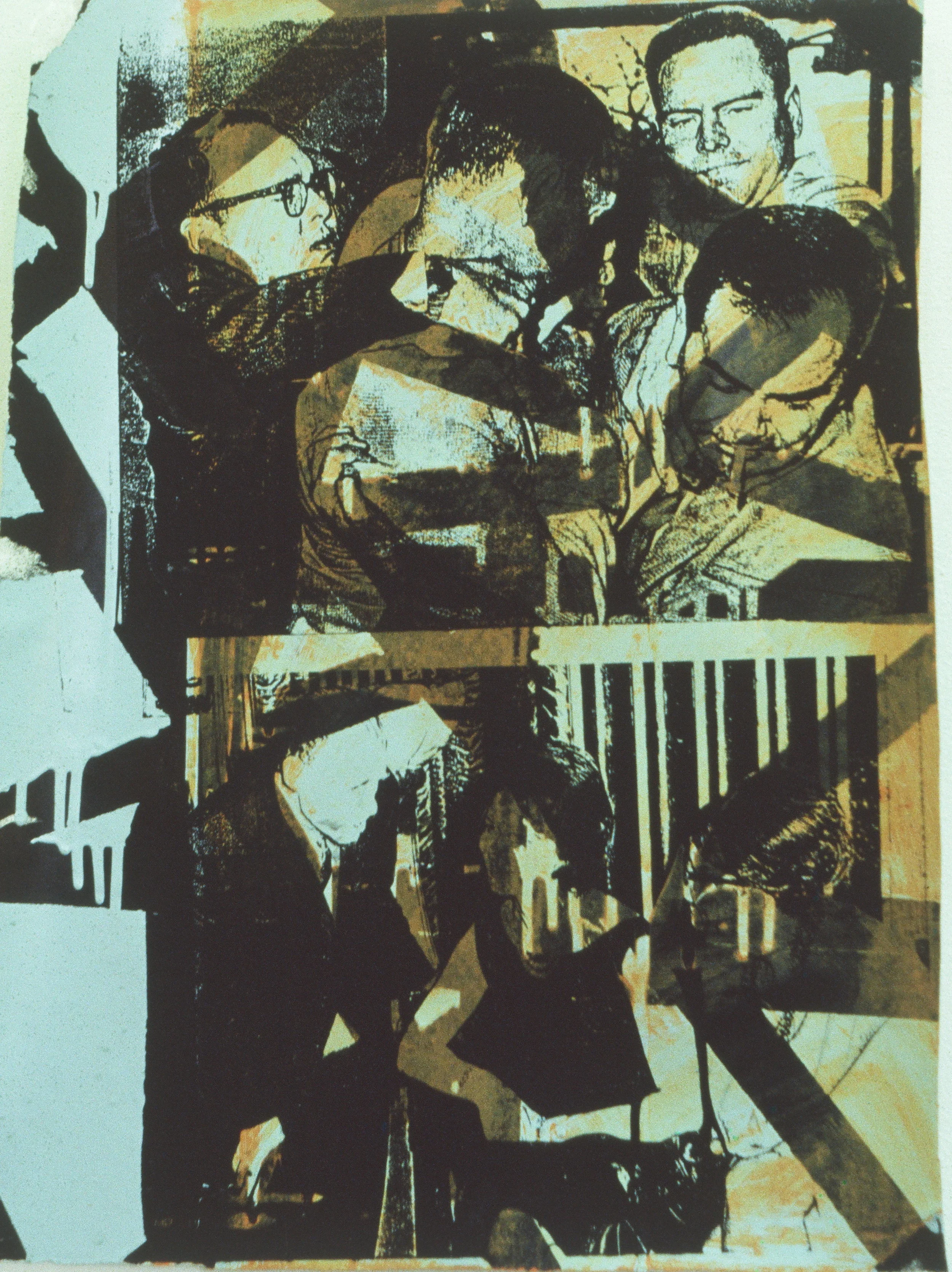

‘A Question of Placating Sycophantic Artistic Consumerism’, 2006

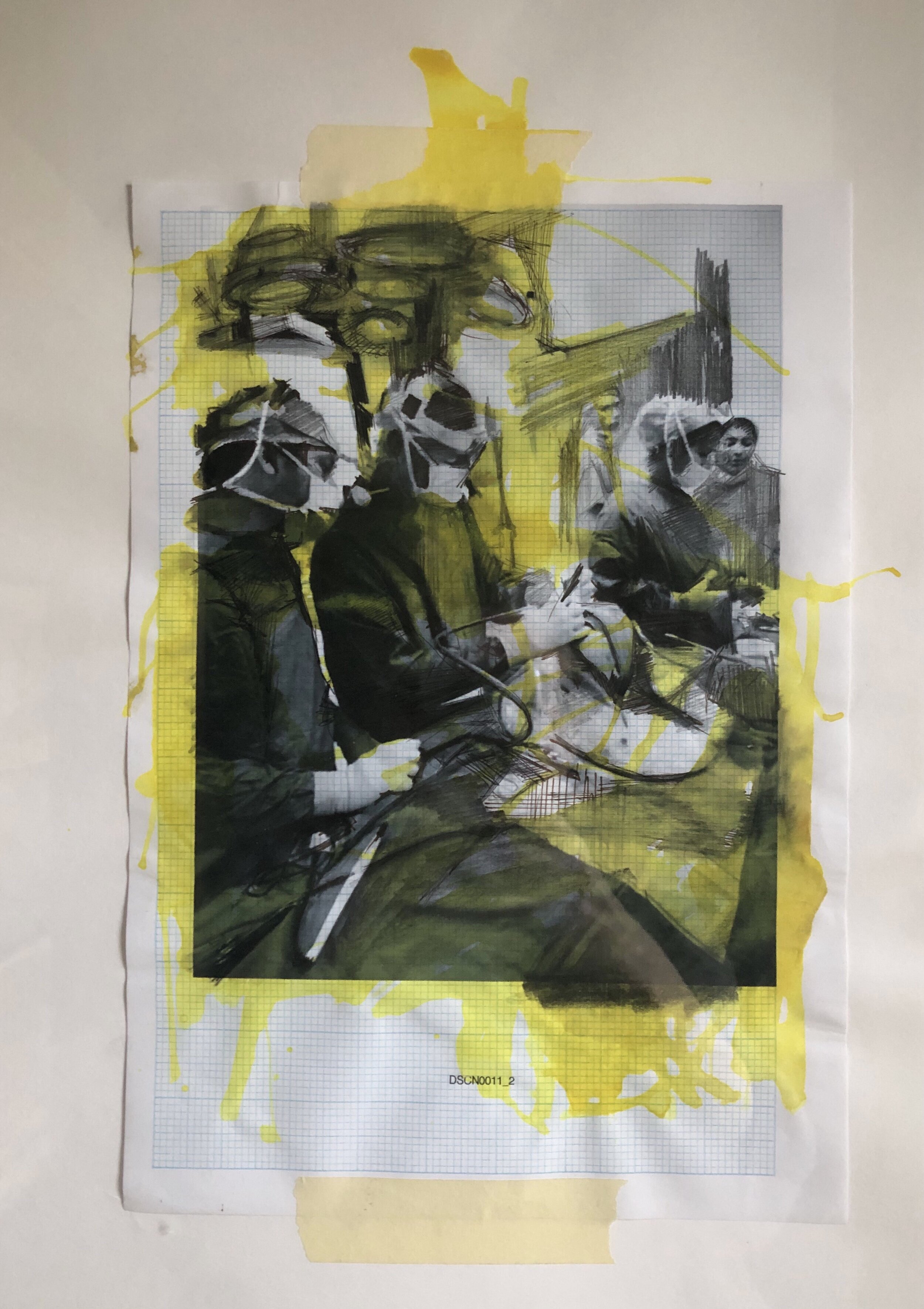

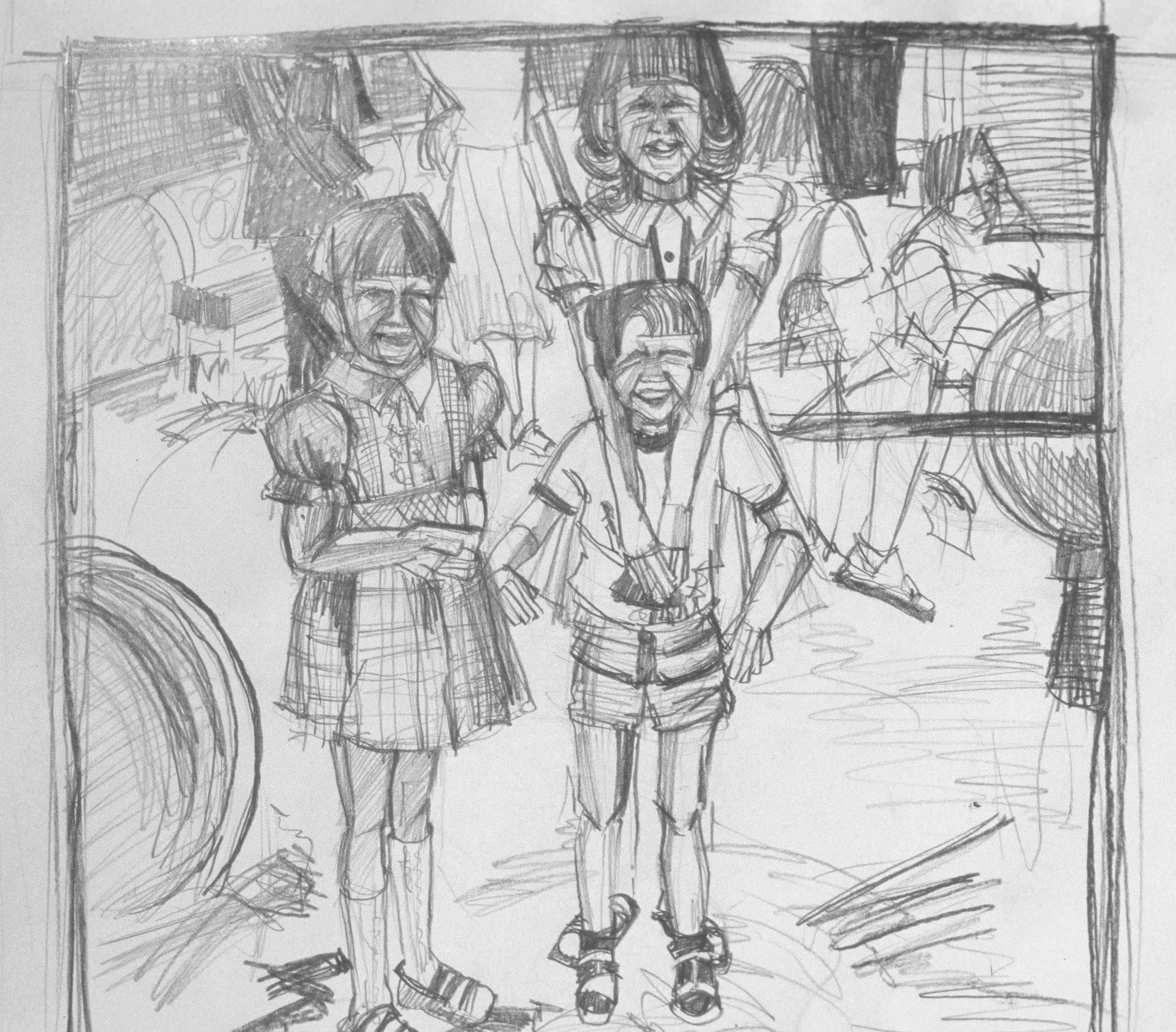

1. Twin 1, 10mm PVC colour image, 380 dpi print, 29.5” x 22”

2. Twin 2, 10mm PVC colour image, 380 dpi print, 29.5” x 22”

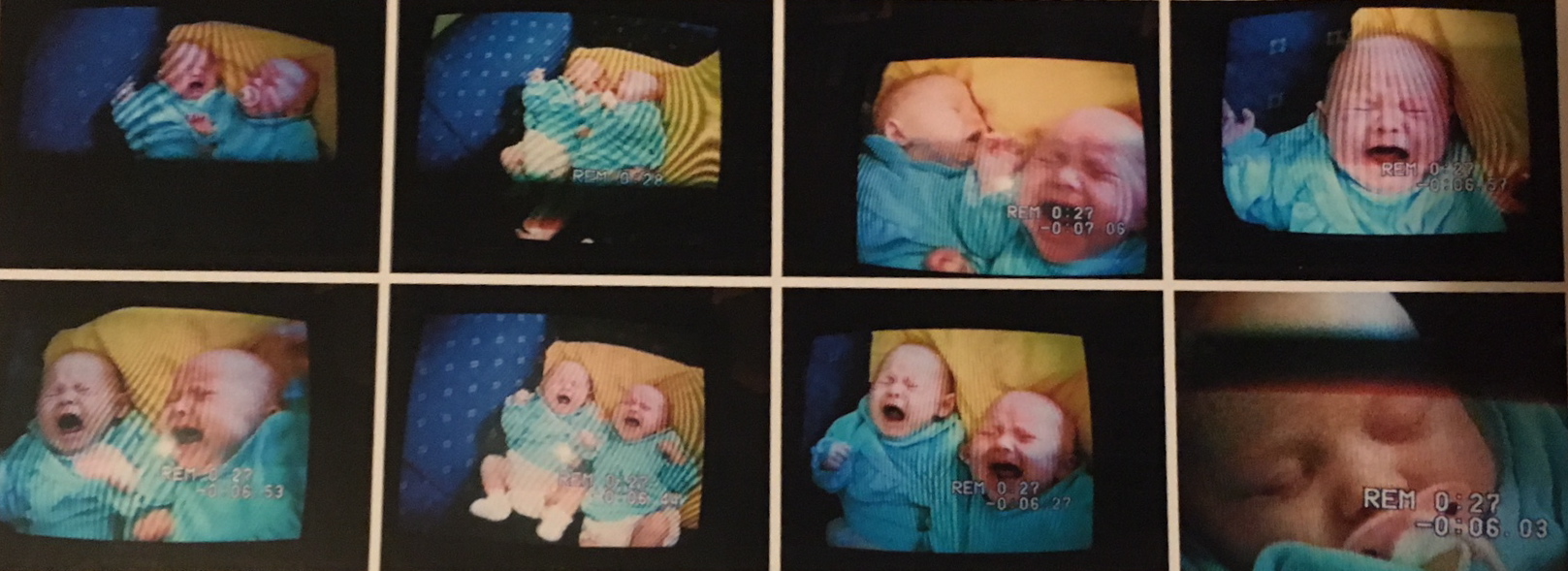

3. Crying Twins, looped (1999) DVD, converted VHS video installation in boxed construction

‘An Investigation of Philosophies on Art’

or

‘Everything I know in life about contemporary art practice, I learned from the writings of one Stephen Patrick Morrissey’

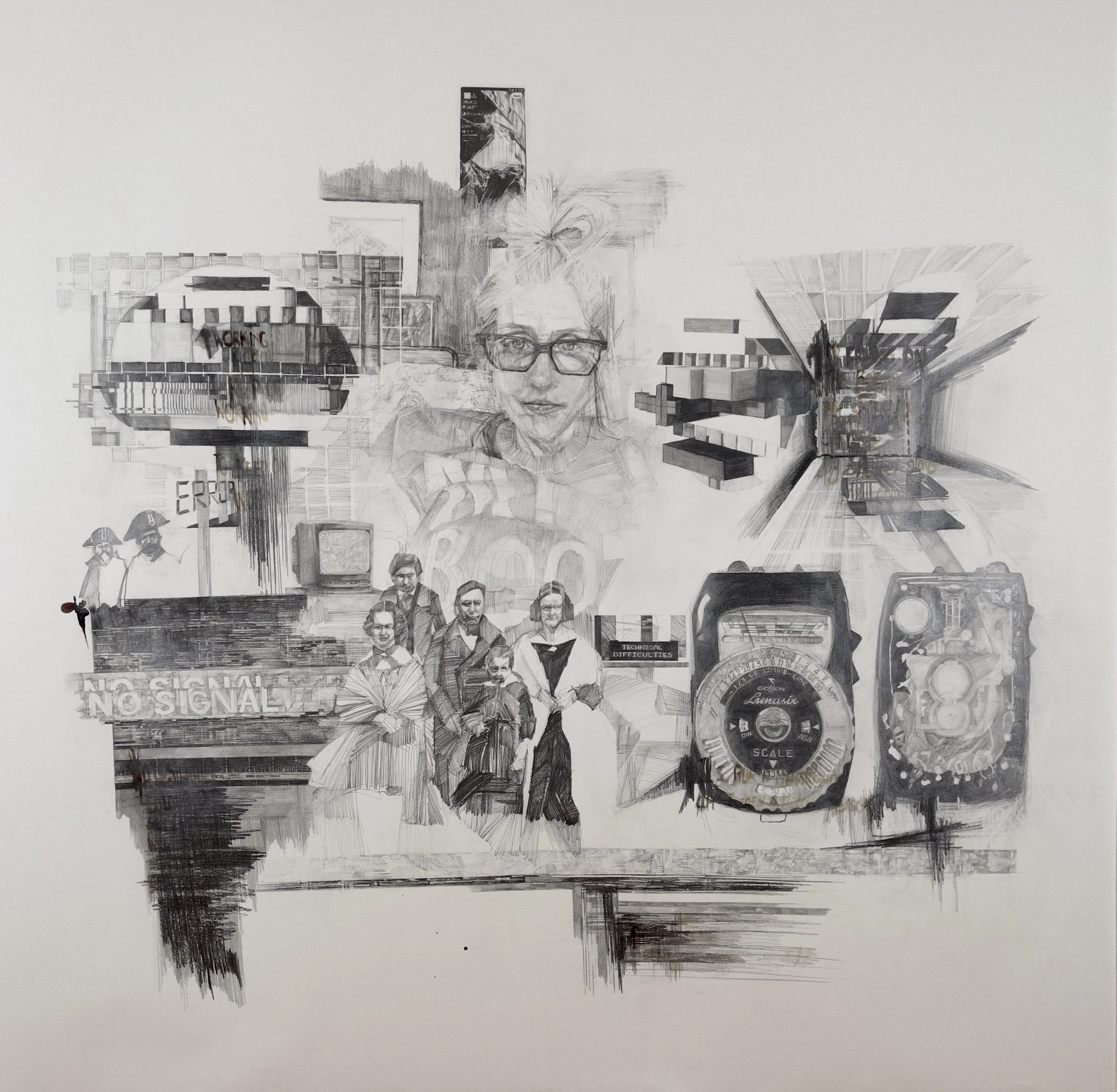

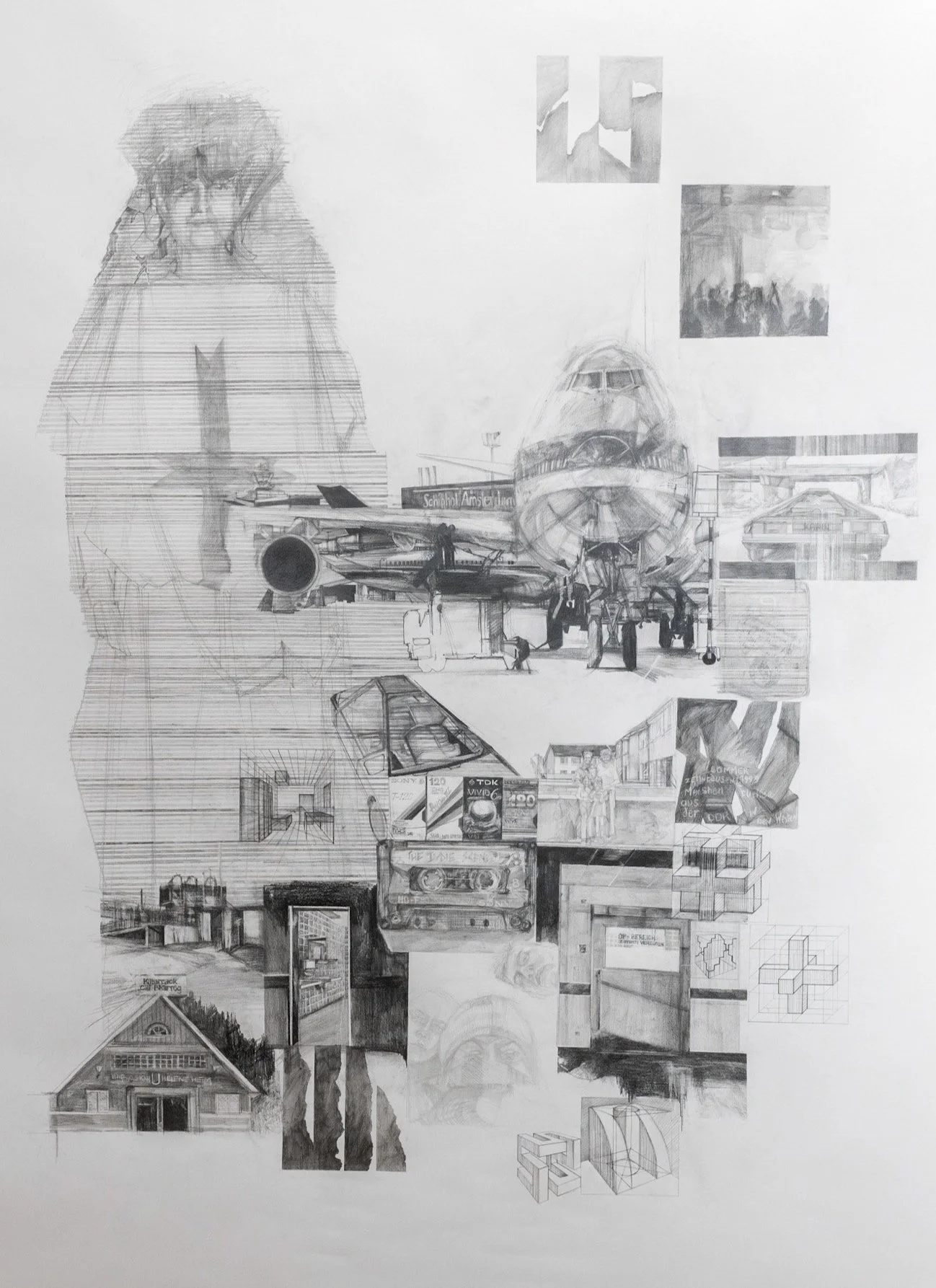

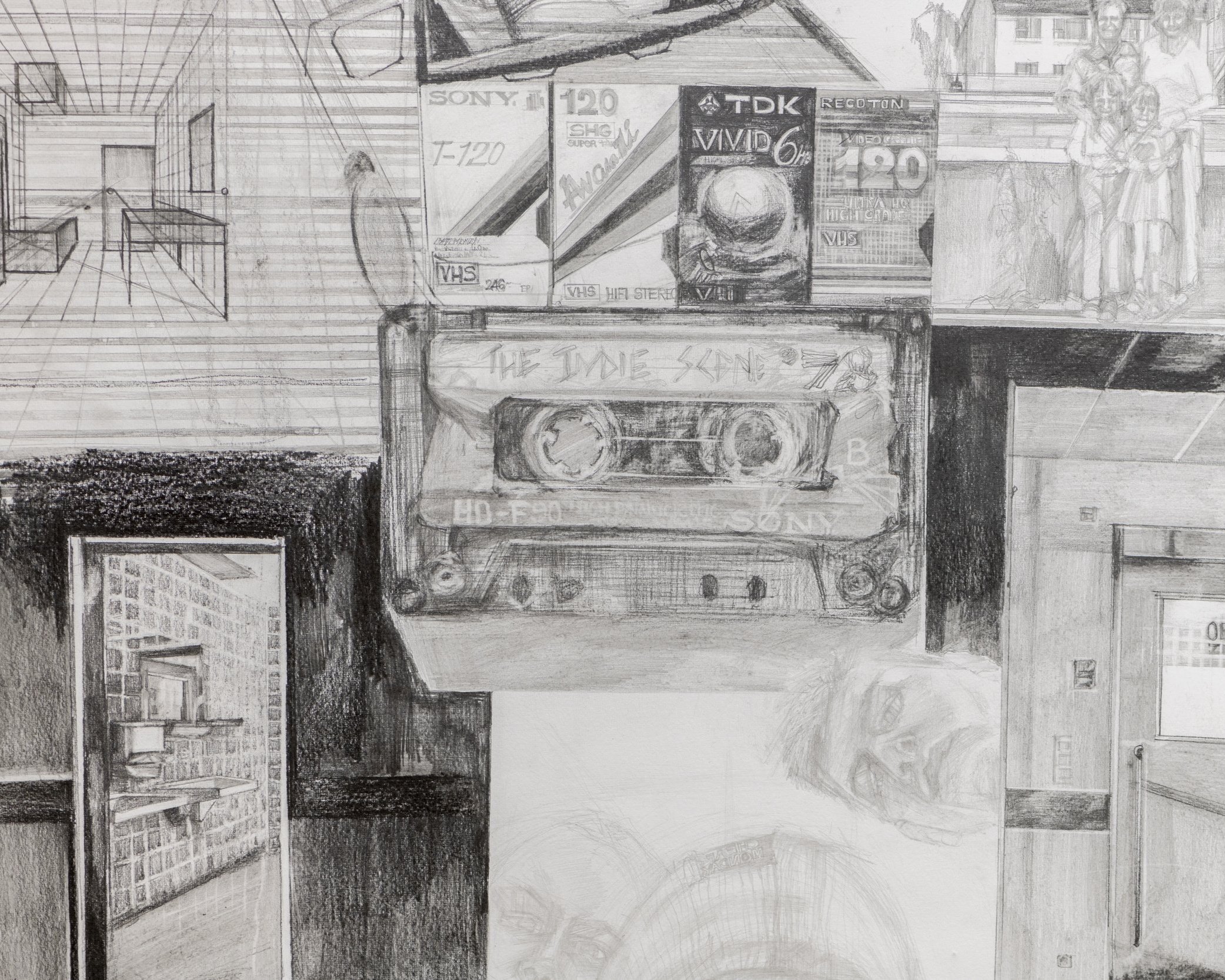

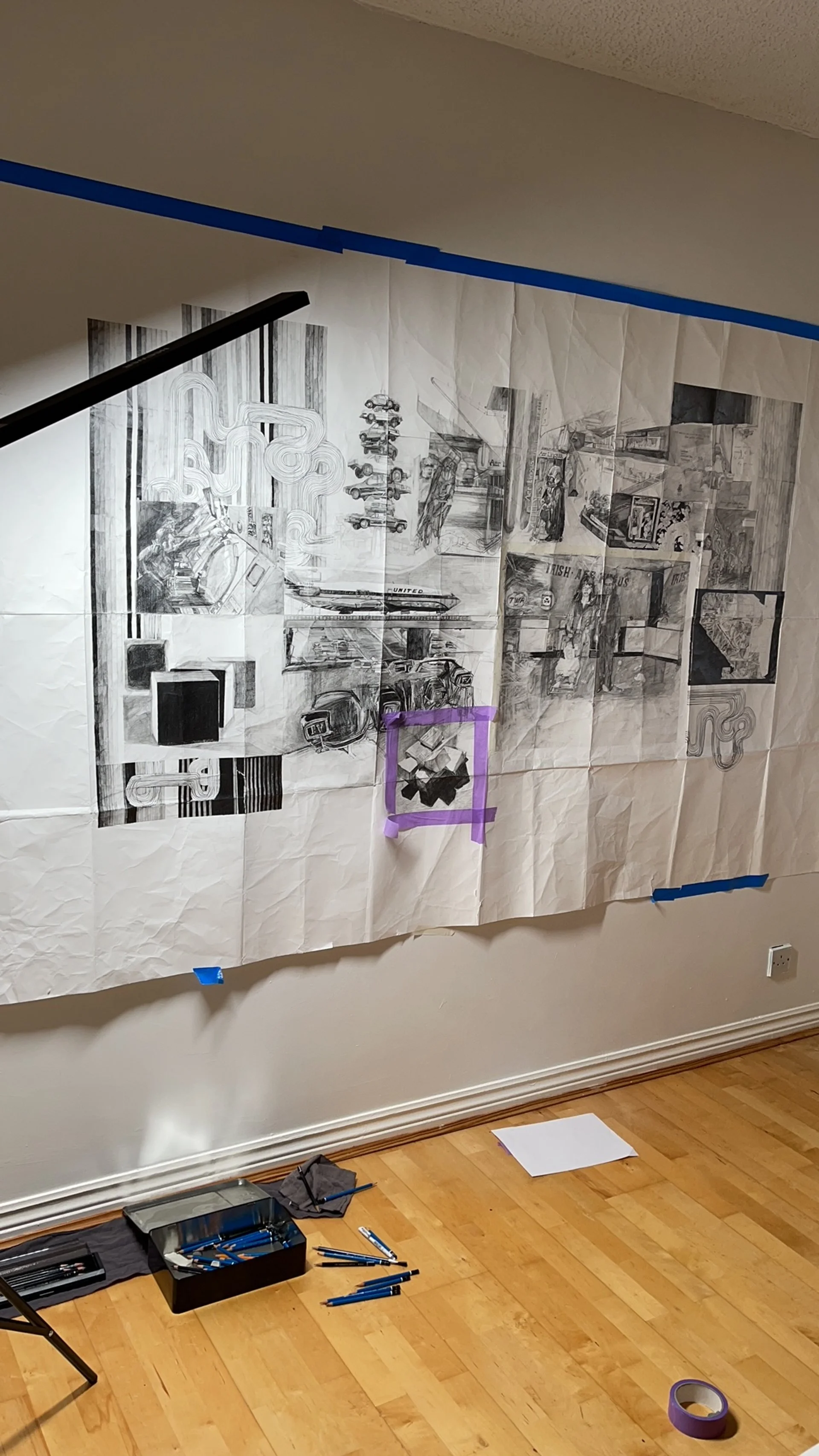

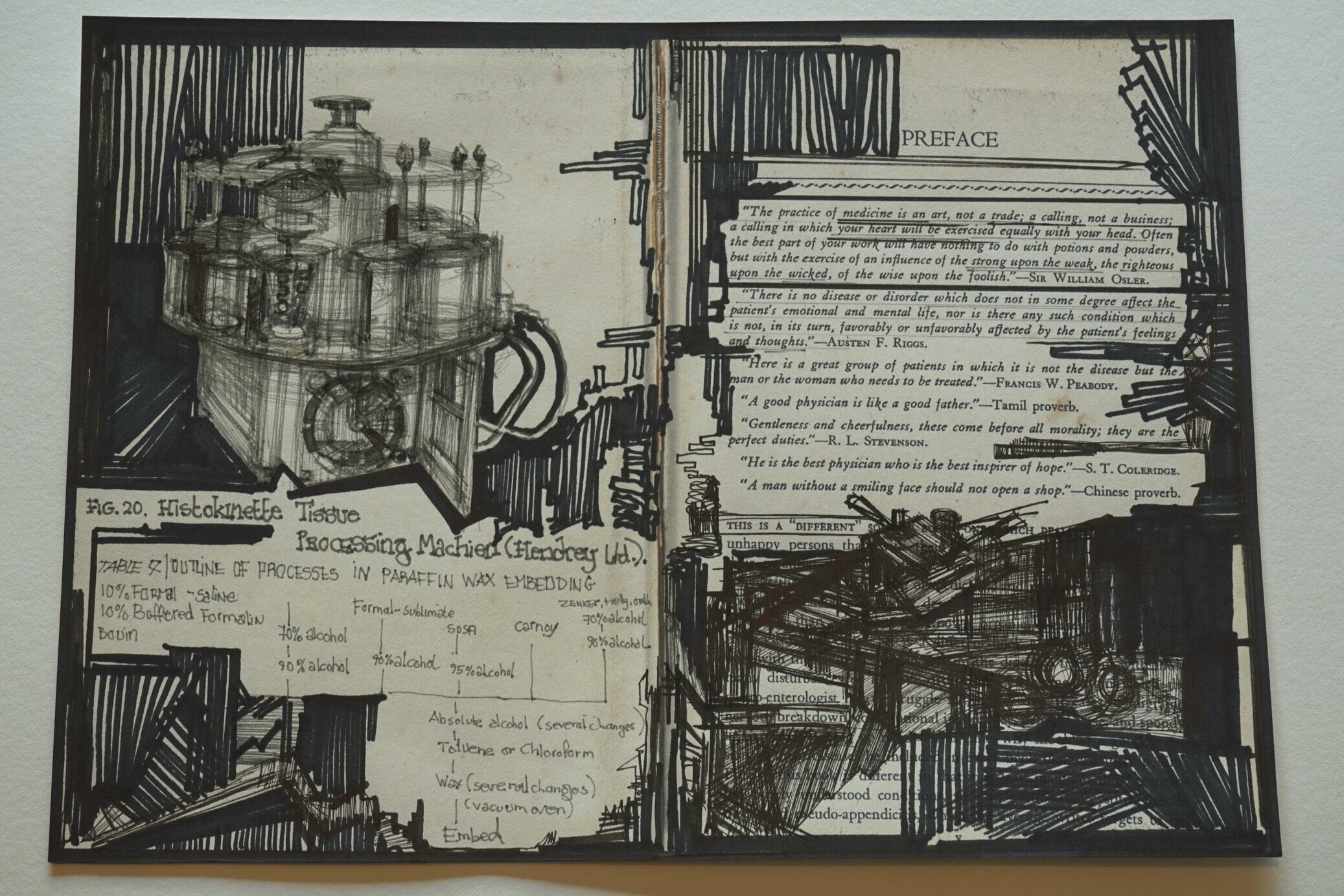

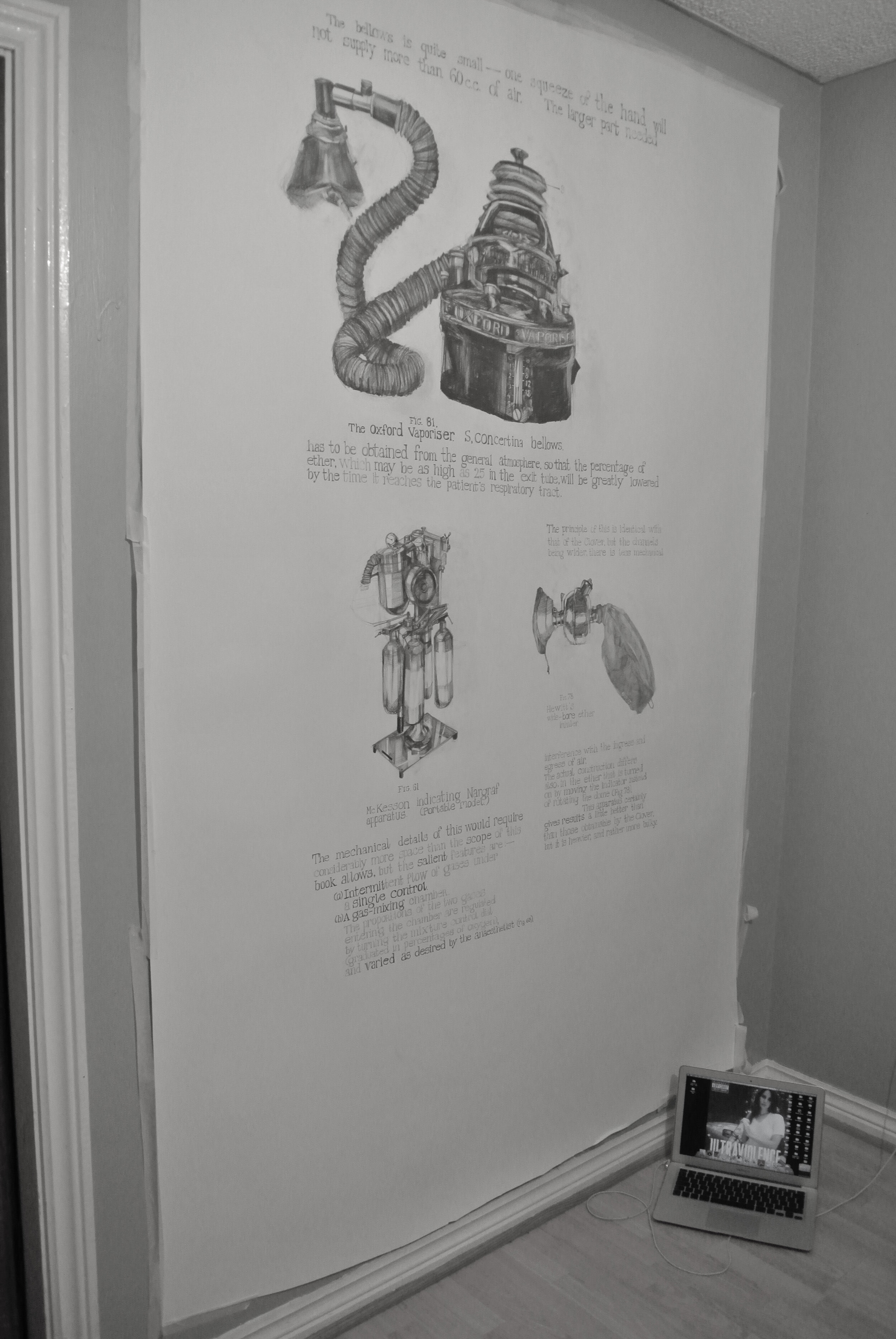

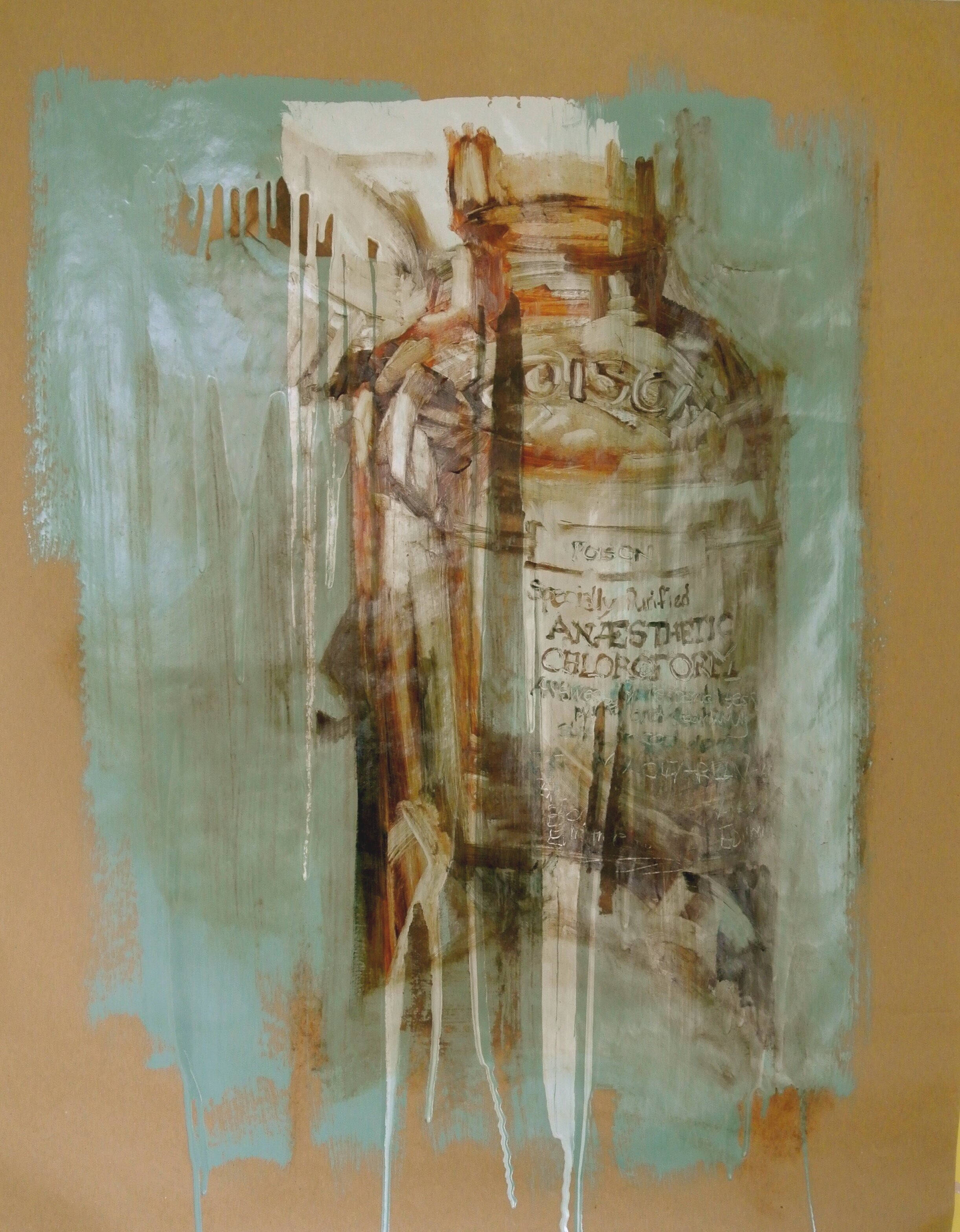

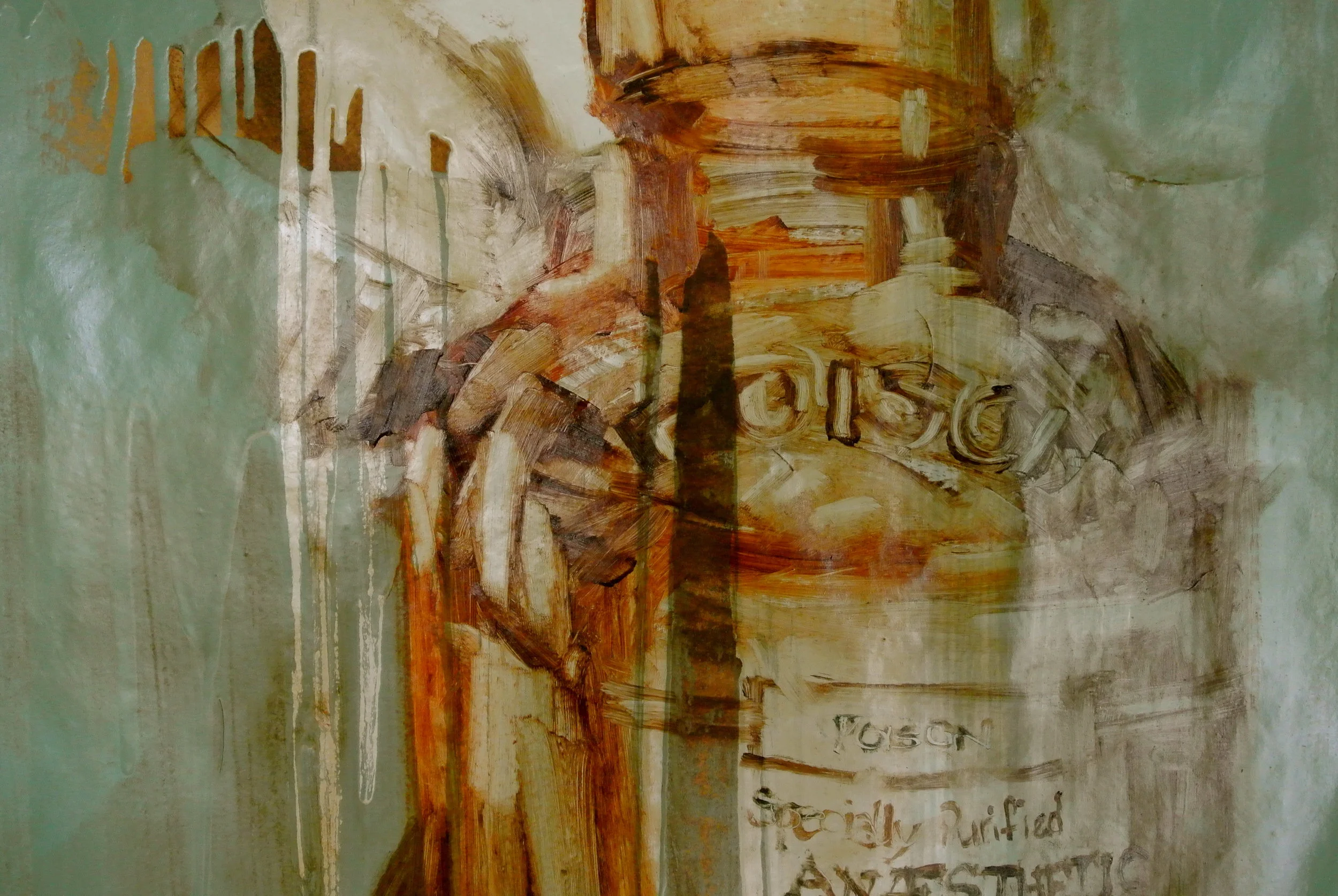

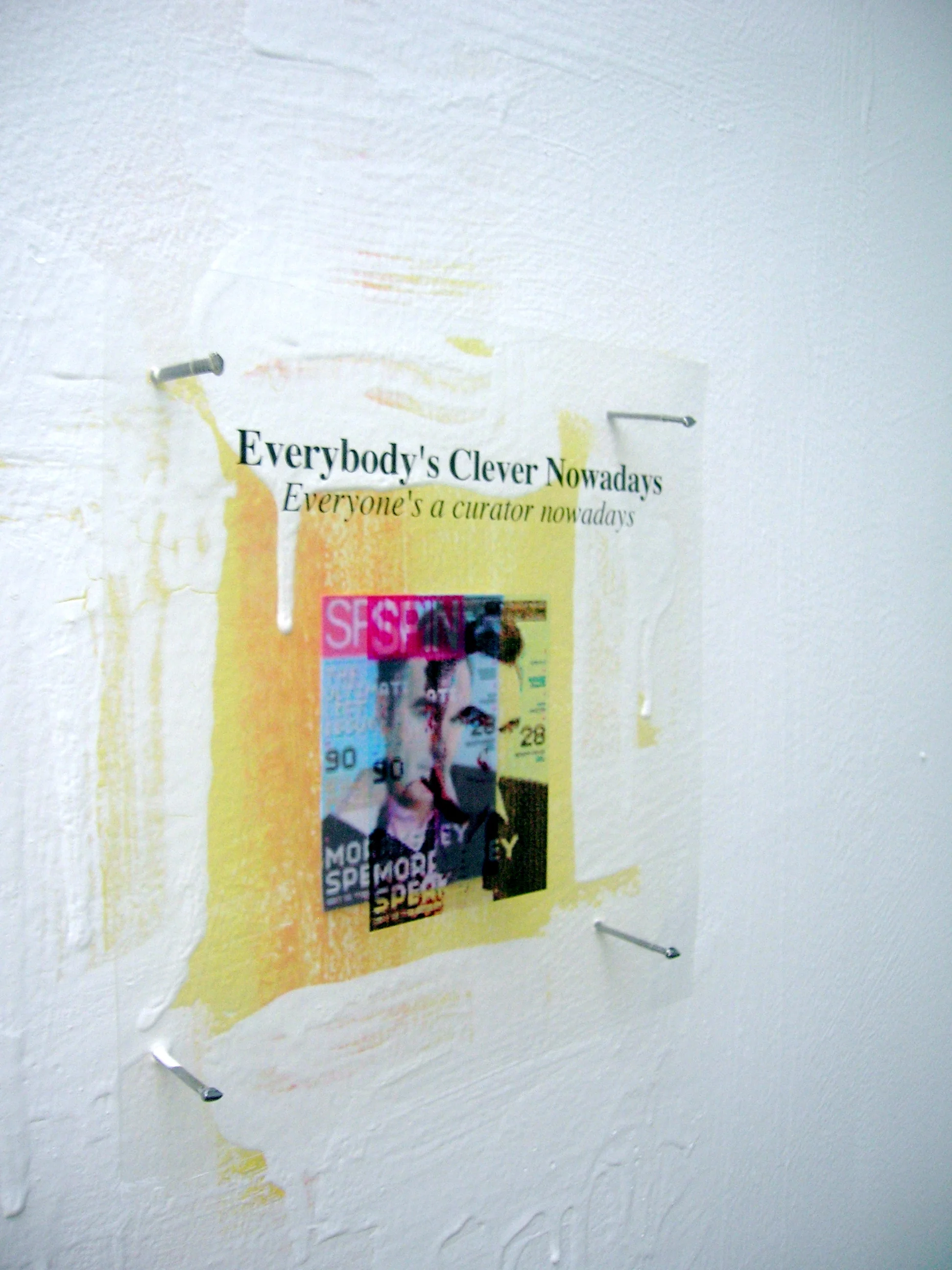

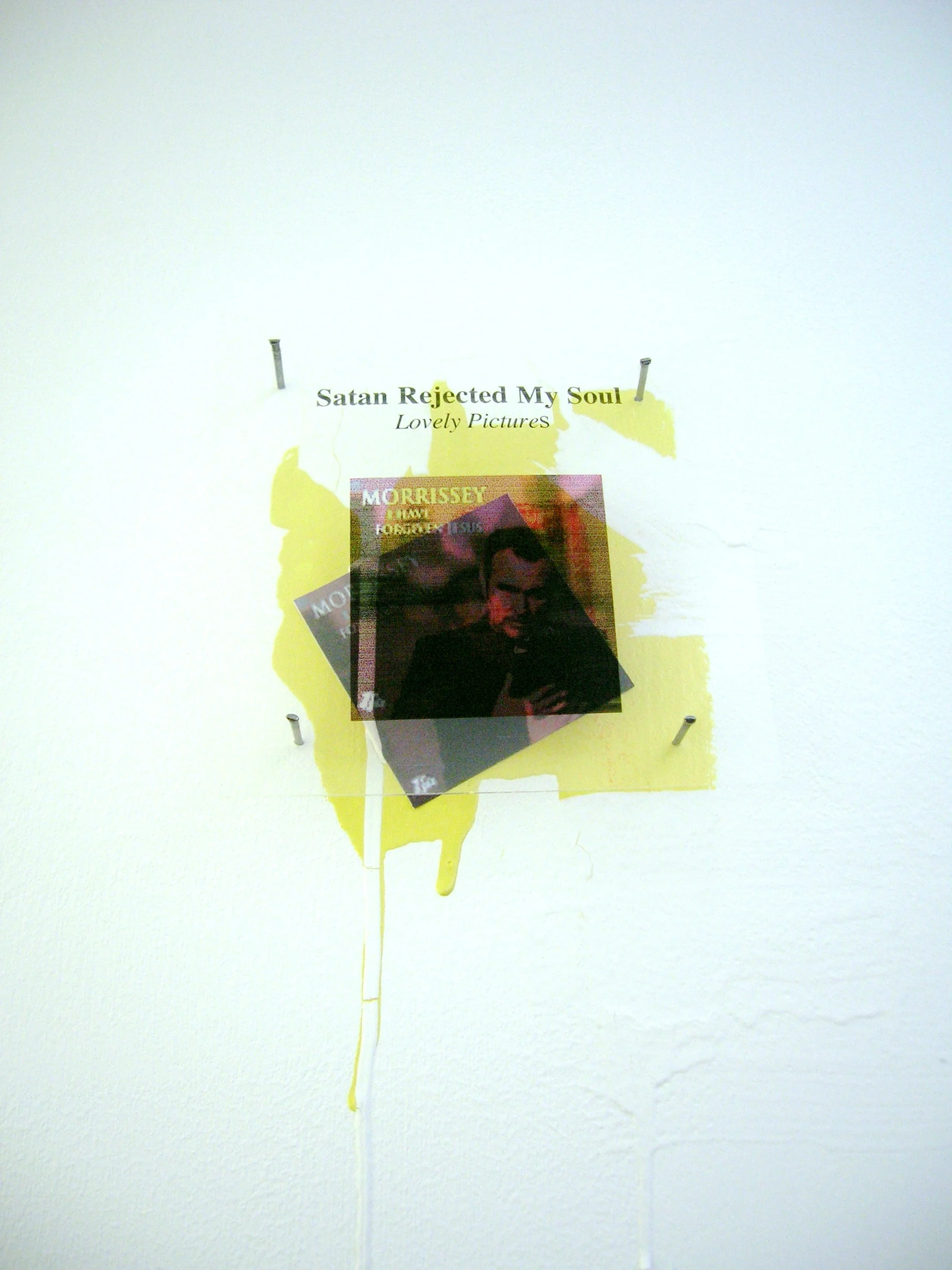

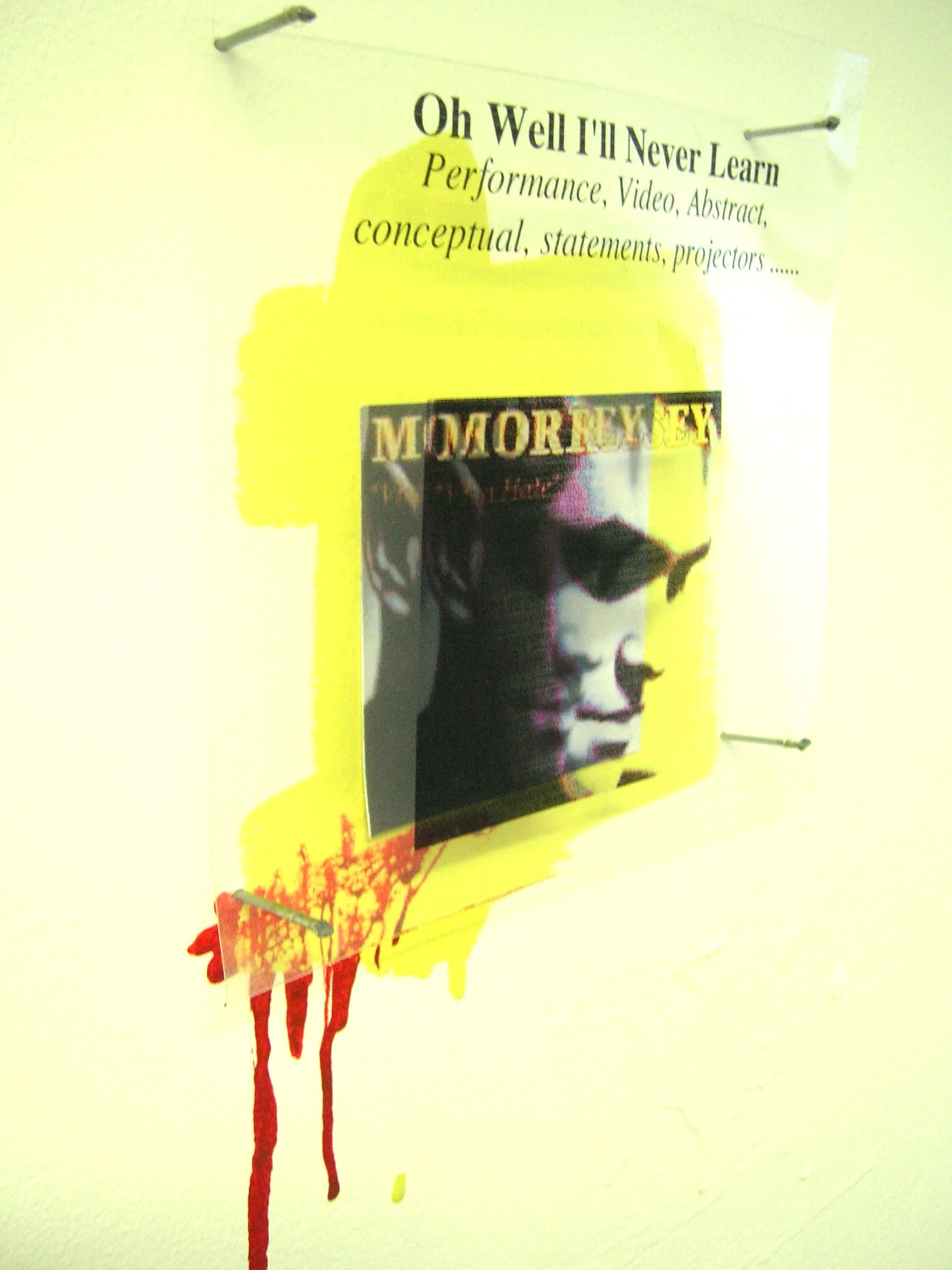

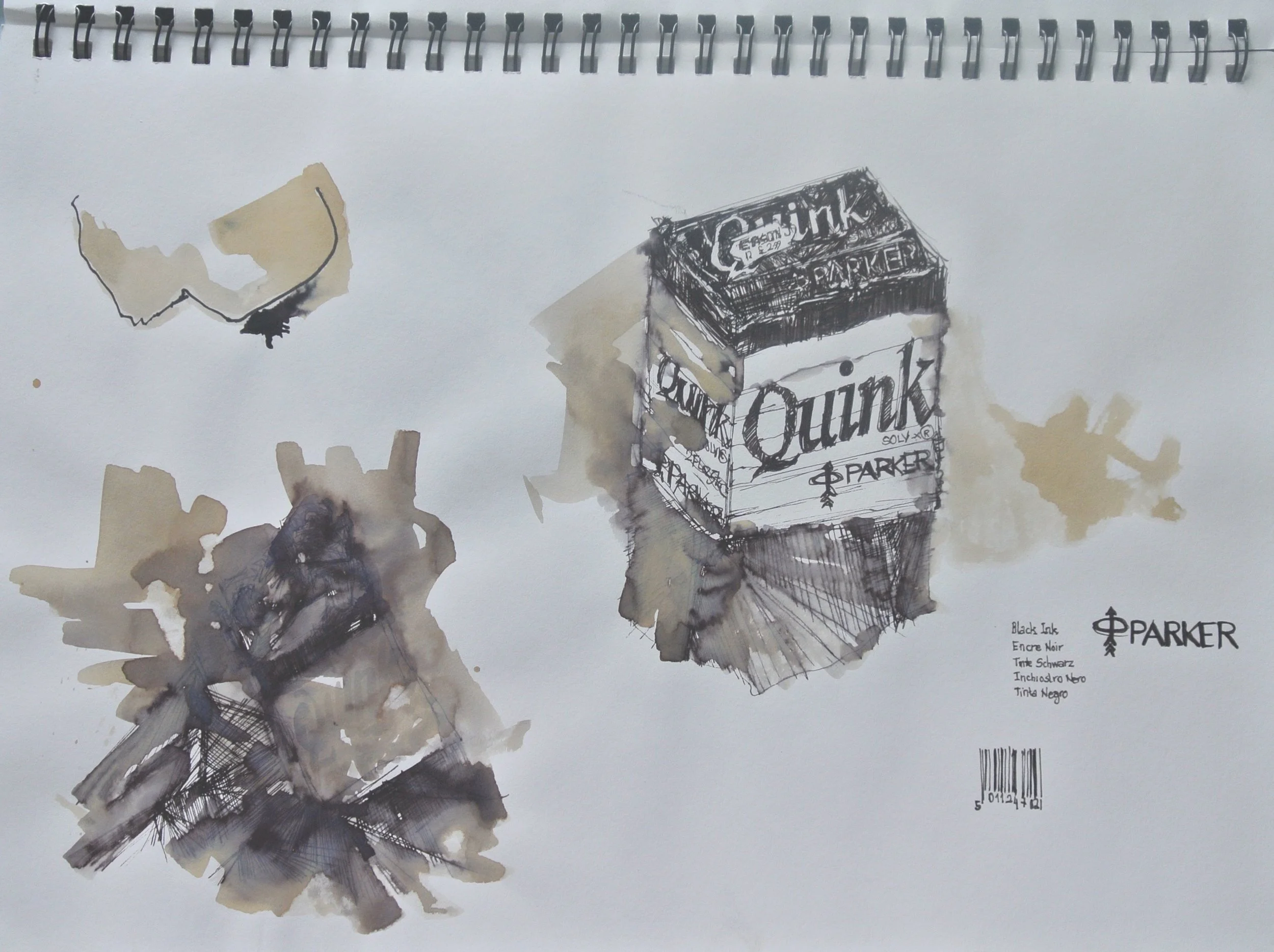

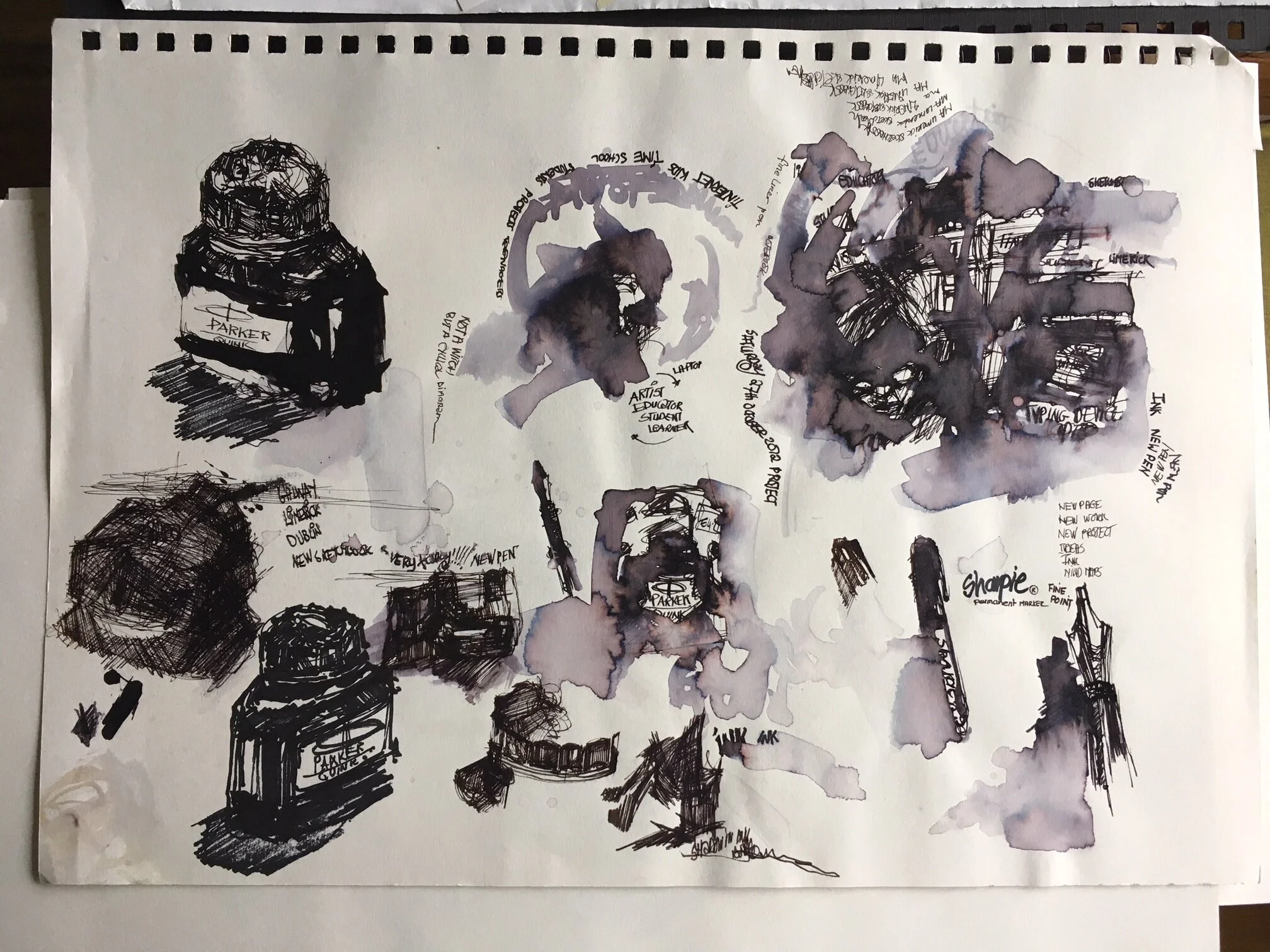

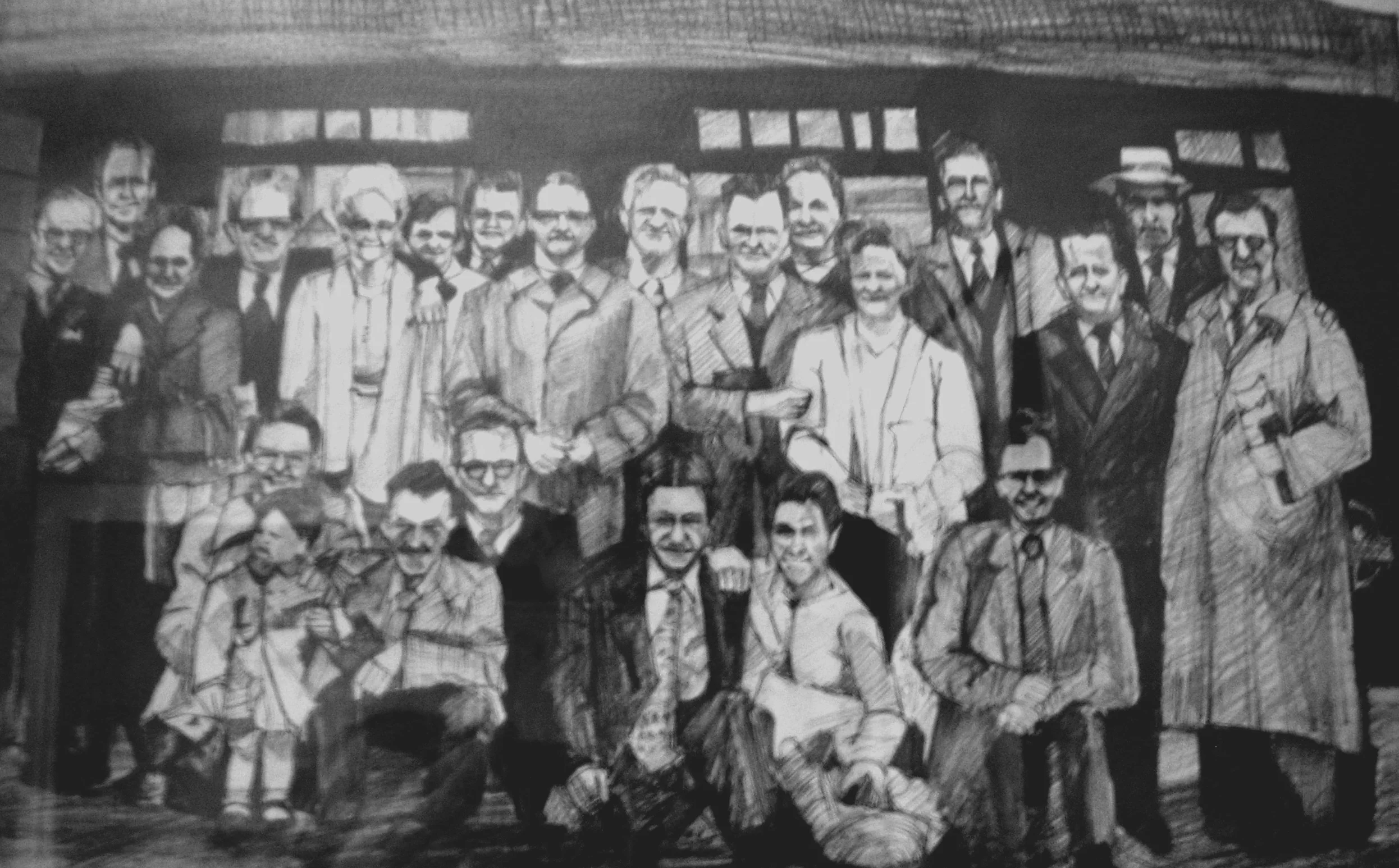

12 x Mixed Media Images on Wall - photocopies, acetate, paint, ink, nails

Response 2018 by Lauren Conway, IADT

Morrissey is often described by critics along the lines of a snotty teenager, sitting amongst the guests at his parent’s dinner party, egregiously making his opinions known above the ripples of polite conversation. This show is the same, although that does not necessarily mean these opinions are incorrect.

There is something inherently punk about the work in ‘A Question of Placating Sycophantic Artistic Consumerism’, I feel this is something that must be addressed first.

The artist borrows this early punk aesthetic as the pop idol Morrissey did and crucifies each for her own ends. His words and images are nailed to the gallery wall streaked in blood. Informal printing techniques reminiscent of D.I.Y. concert flyers are used while being amalgamated with the sophistication of a Bauhaus treatment of the concept. I’m sure he would love this, much like the singers early aesthetic, the work bleeds with a sort of sophisticated defiance.

‘Placating Sycophantic Art Consumerism’ is a homage to defiance, the artist borrows the pre UKIP/Brexit Morrissey as her moral framework, specifically solo career Morrissey when his lethargy with the status quo truly came into its own (see tracks ‘Irish Blood, English Heart’ ‘The World Is Full Of Crashing Bores’). Initially, these acetate ‘stations of the cross’ seem to have no connection to the second installation, photographs of two young girls and a looped video piece featuring the piercing screams of newborns babies.

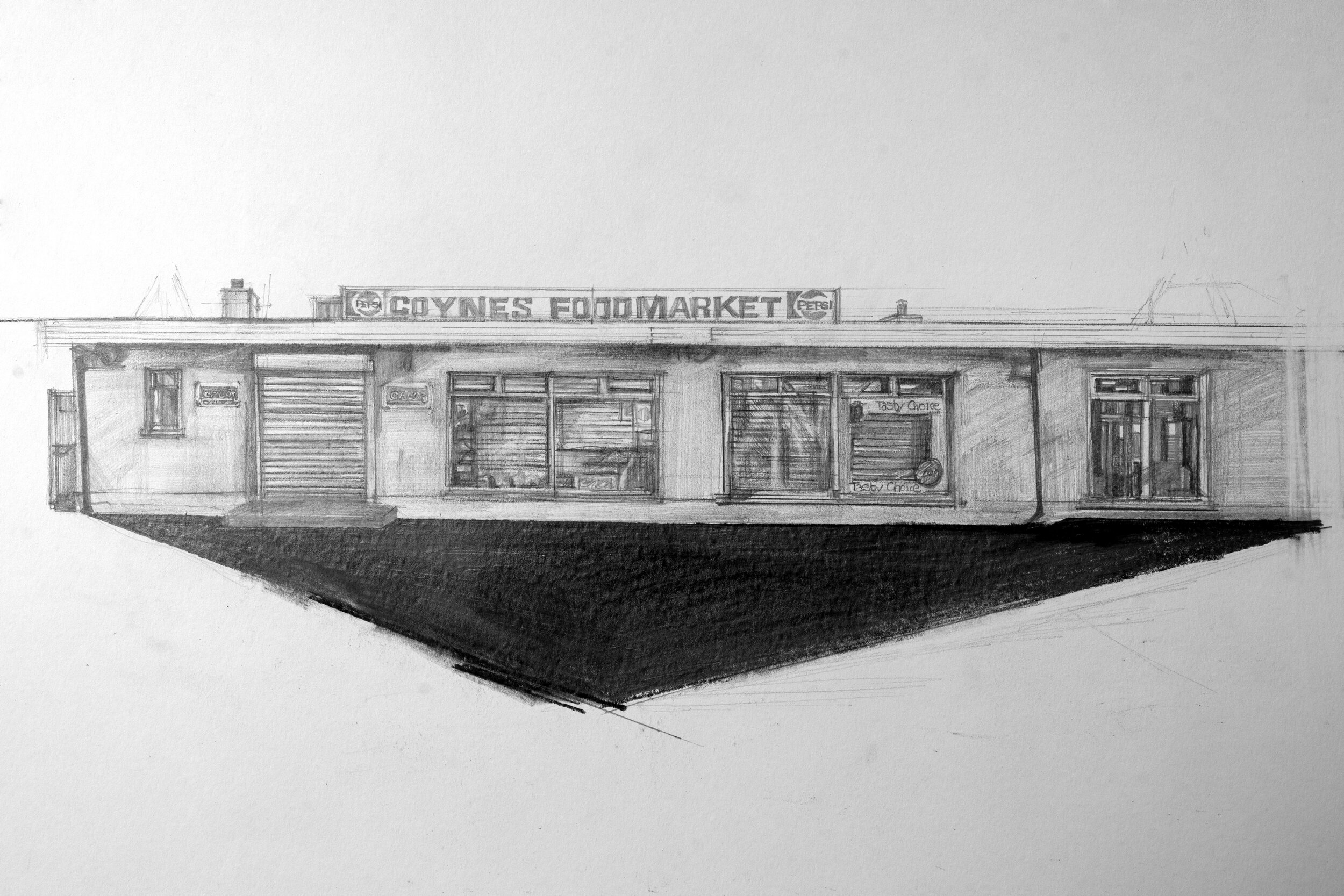

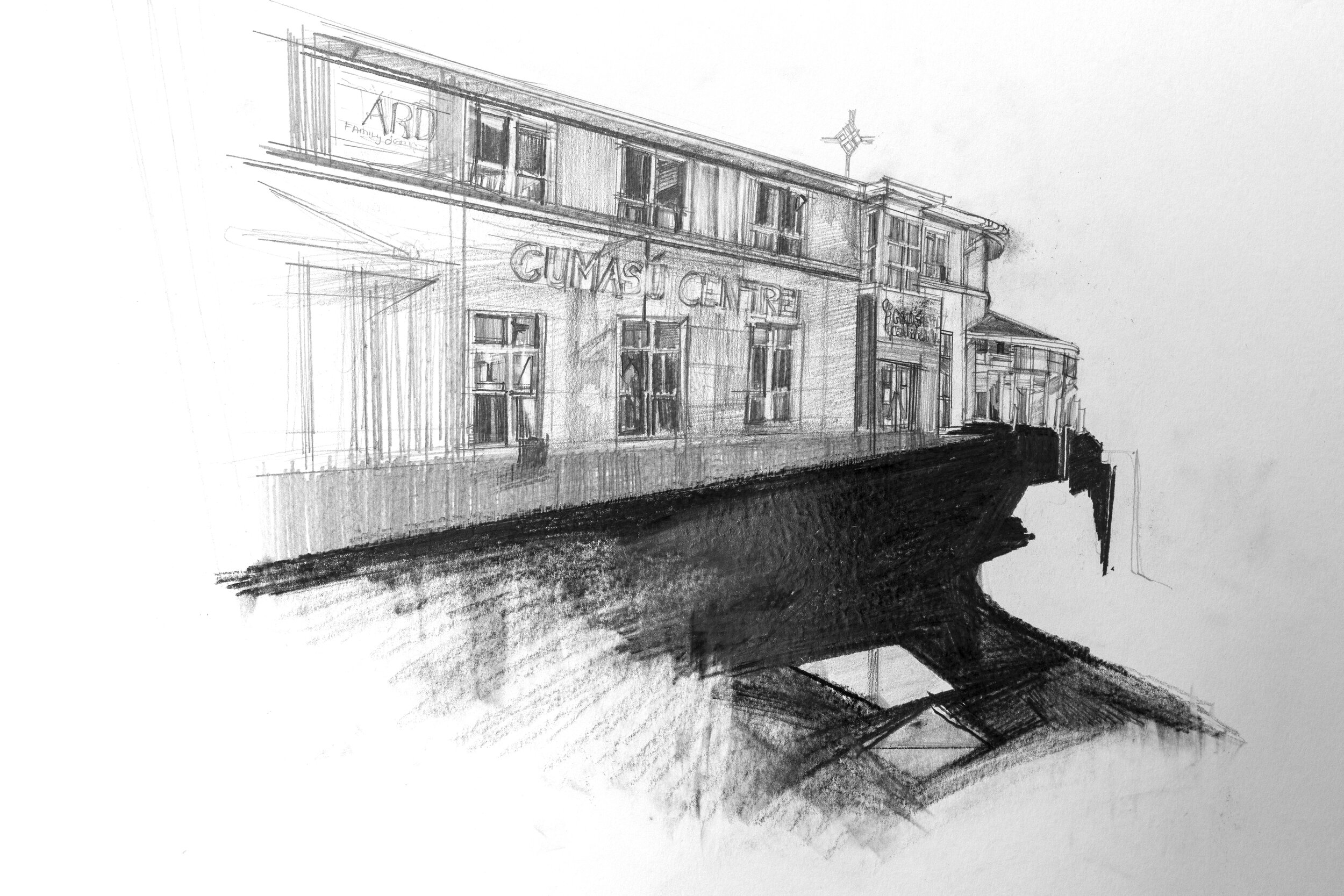

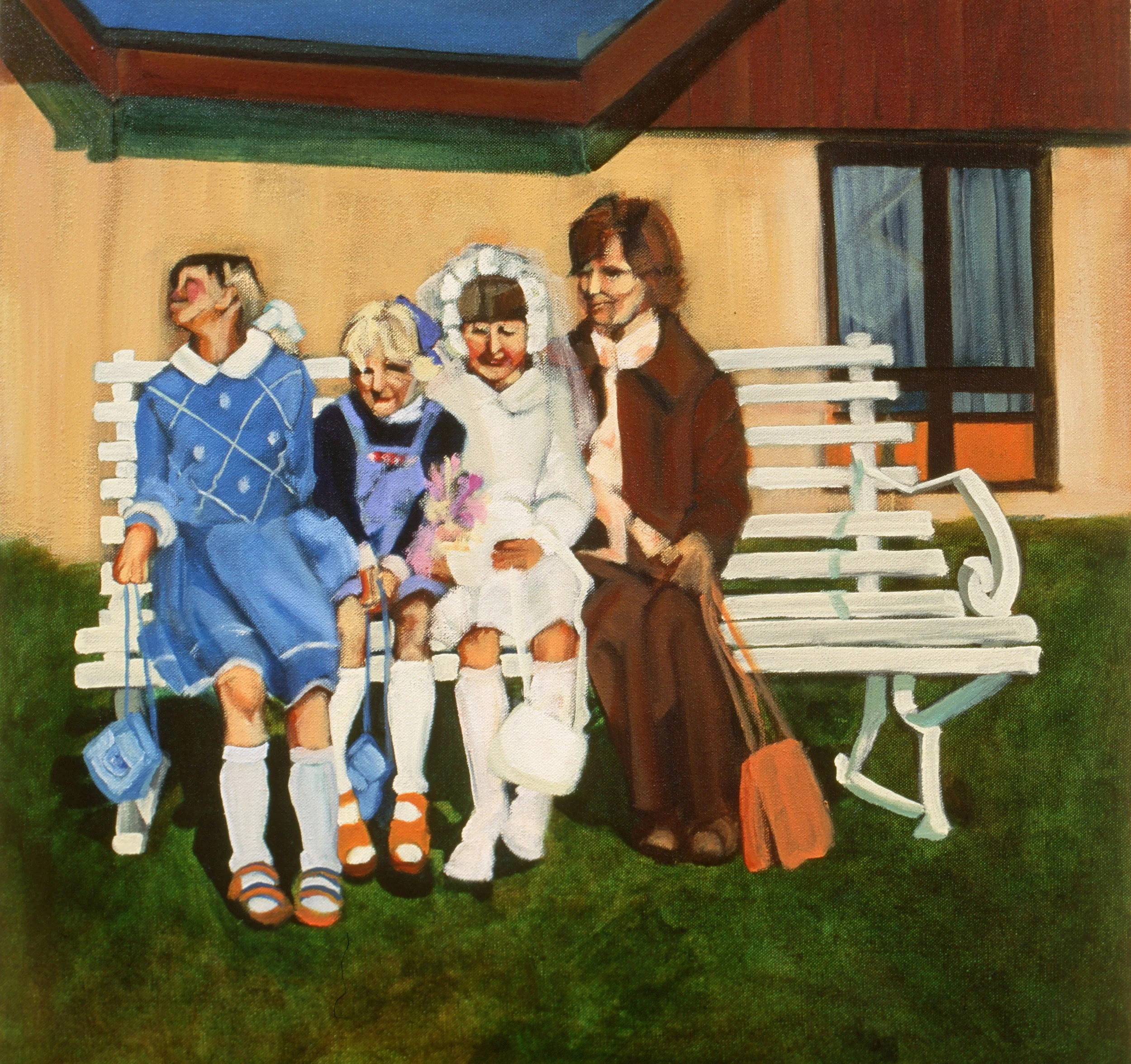

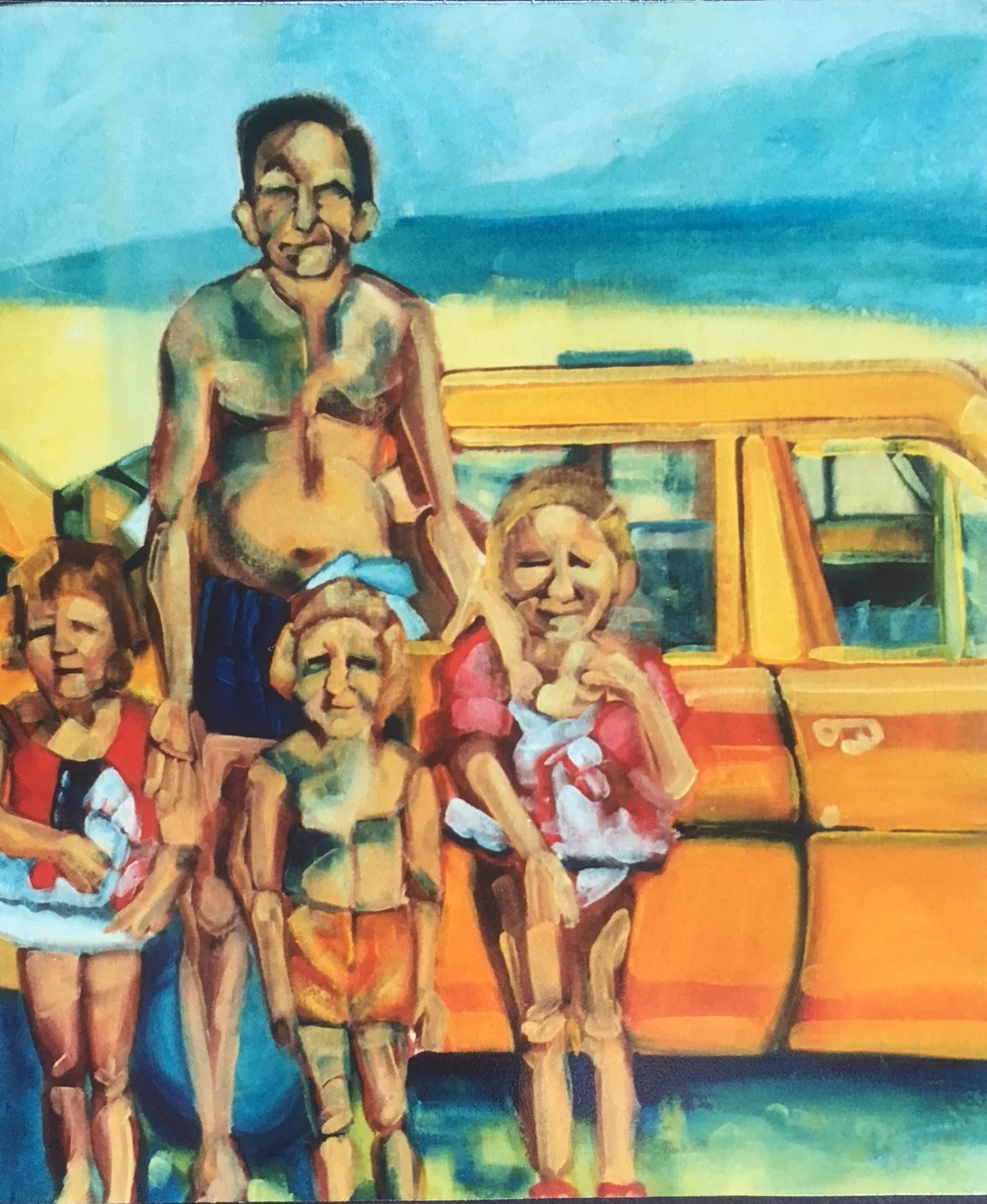

In ‘Twin 1’ there is a defiant stare, a cheekiness thrown straight back to us, the objectifier, while ‘Twin 2’ attempts quite ineffectively to appear as though she does not realise she is being watched. Can we can see the artist herself in these portraits, watching us watching her. The artist and figure await the reception of the audience as Morrissey does, with a similar aura of apathy and a cavalier demeanour.

On a darker note, in the work ‘Twin 2’, the figures avoidance of the audience, her desire to step outside the role of “object of vision, a sight” recalls the now infamous essay by John Berger in his landmark book ‘Ways of Seeing’.

“From earliest childhood she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually. And so she comes to consider the surveyor and the surveyed within her as the two constituent yet always distinct elements of her identity as a woman.”

A feeling half of us share.

These are images that exist inside of yet in opposition to the Family Photograph.

They are mugshot.

They are casting polaroid.

They are profile picture.

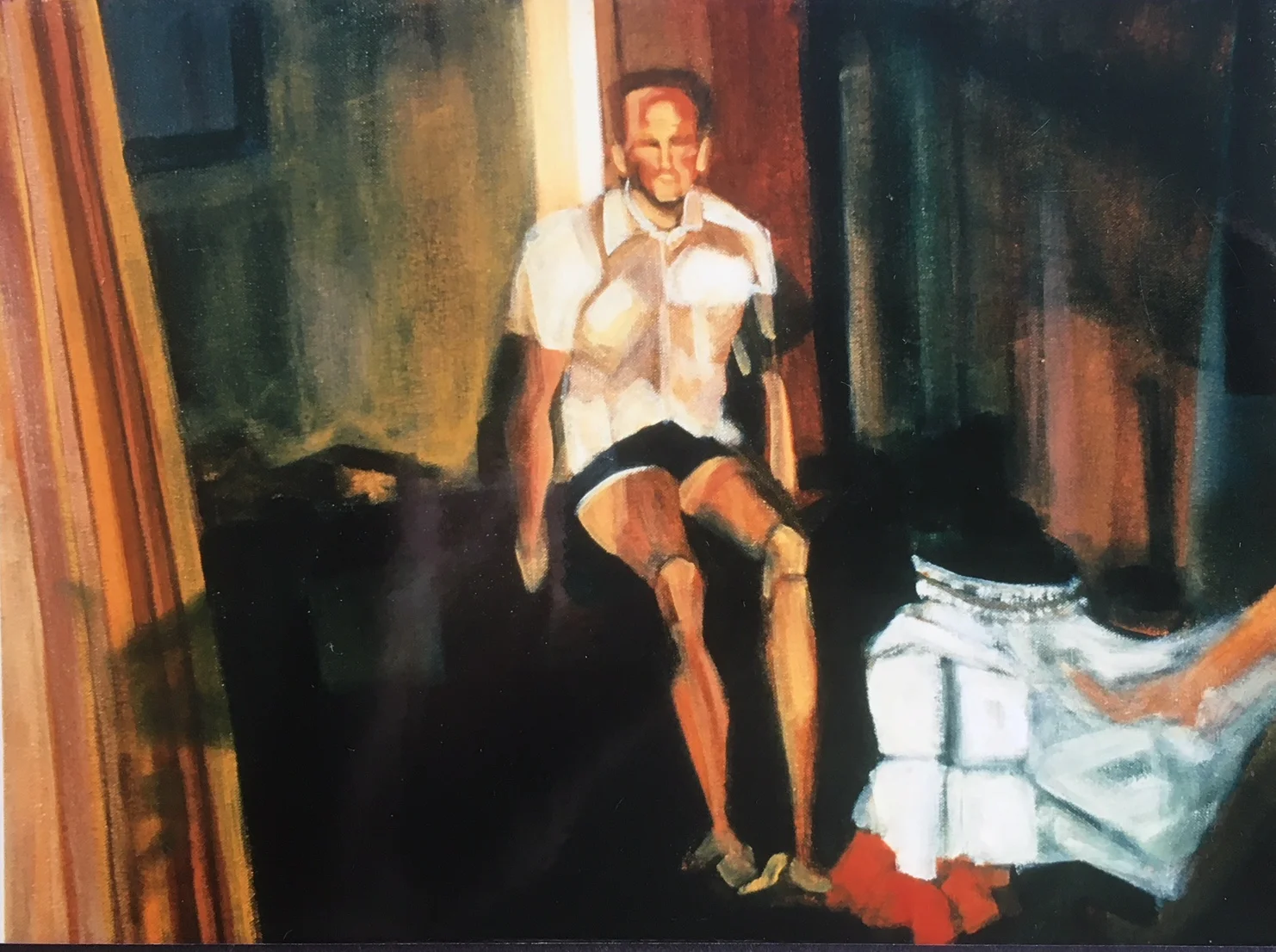

The noise is deafening, shrill, the sound every exhausted parent of a colicky baby knows, there is no off button. Wailing with discontent, like Morrissey himself, we are plunged into the depths of the artist’s gaze and the unsettling way in which she applies it to her infant children. They are specimens to be observed, as she has had to amidst their overwhelming sensory overload, they are not to be passed around a coffee table or objects to be commented upon as ripples of polite conversation. The stills alone invoke, horror, unease, an intense sense of voyeurism. The television screen represents the barrier between their reality and audience’s, highlighting their intense and seemingly infinite suffering as well as our inability to solve this problem we are being presented with. Similar to Morrissey, it is the suffering of an infant, there is no emergency.

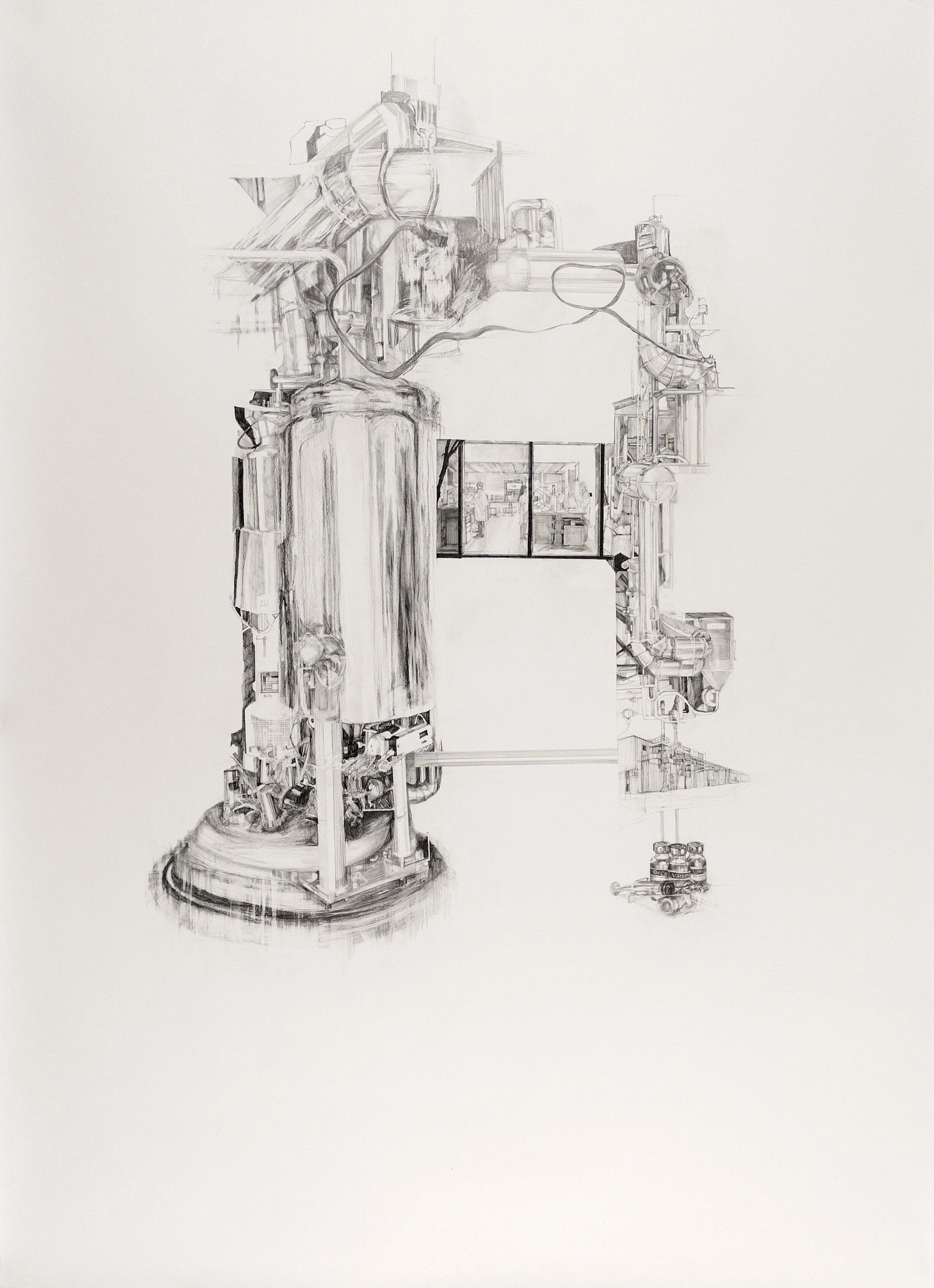

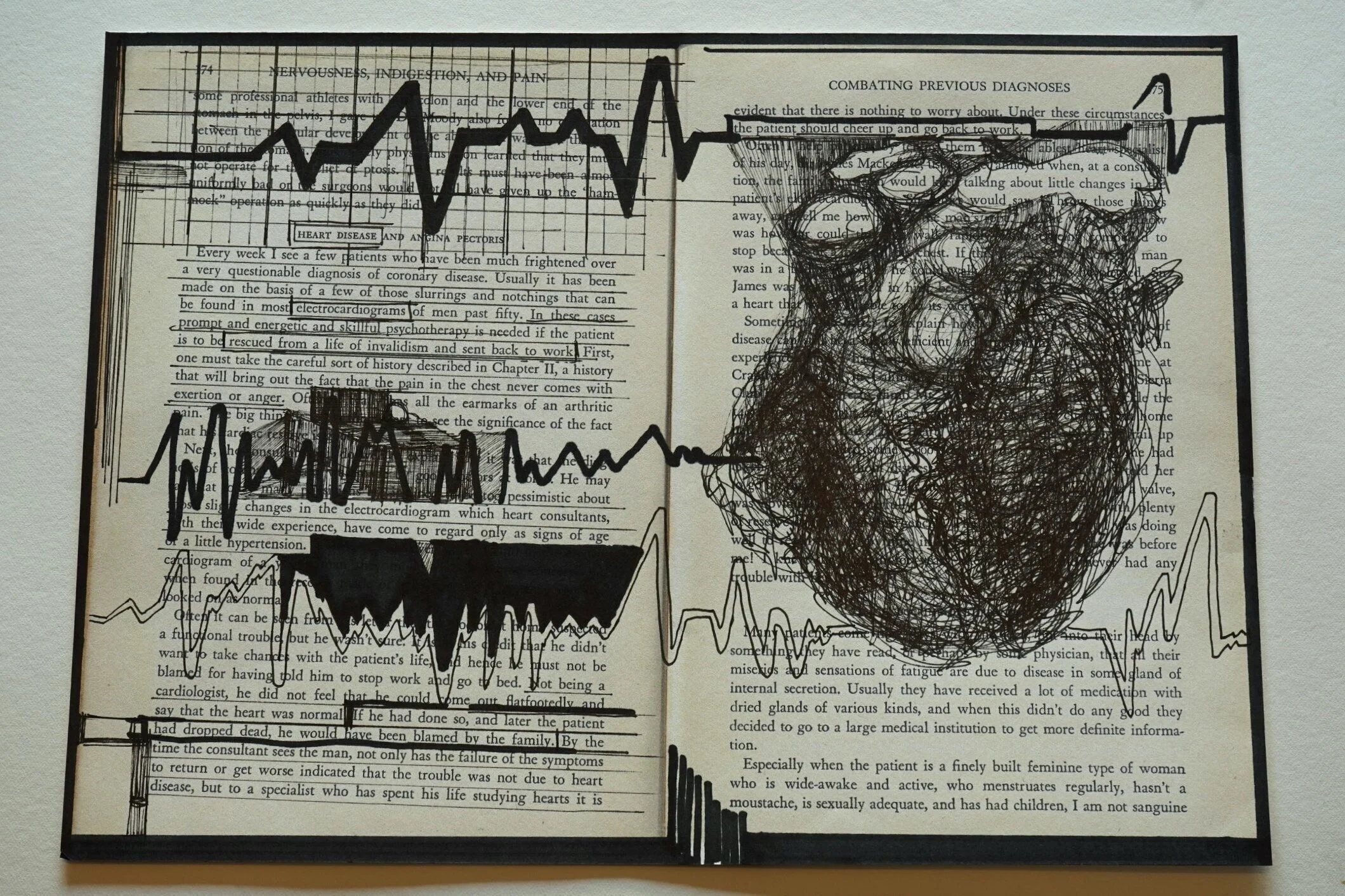

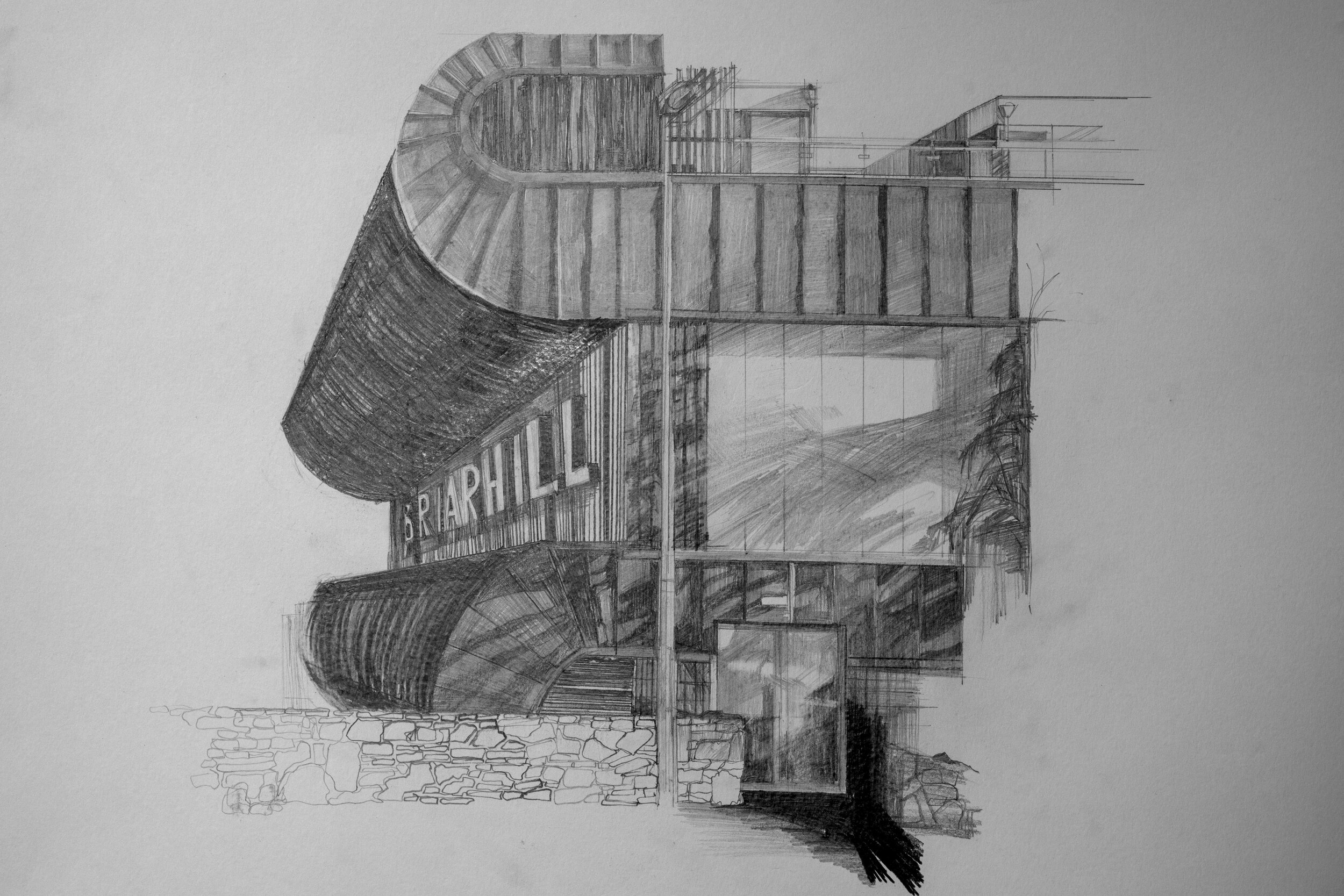

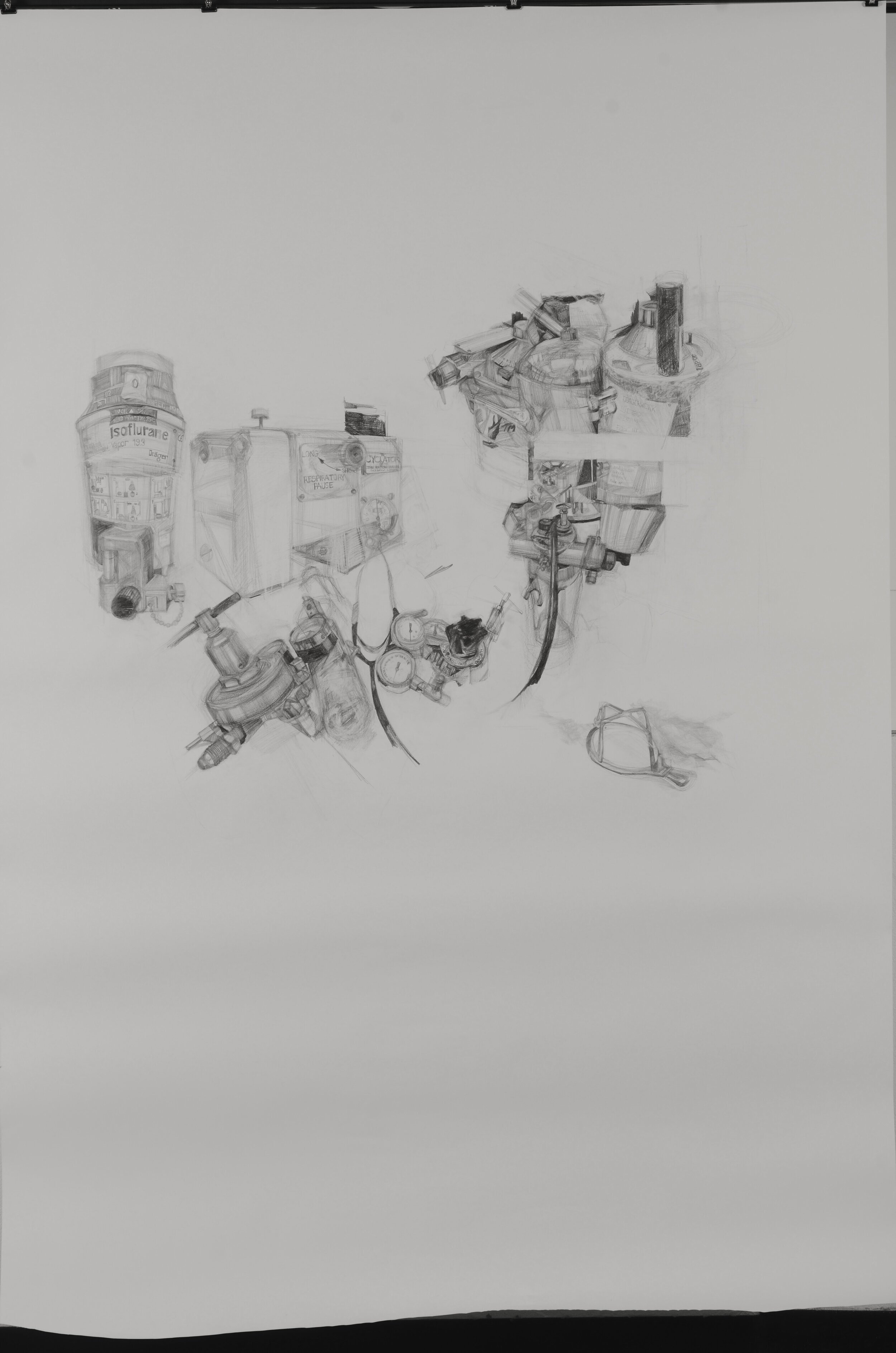

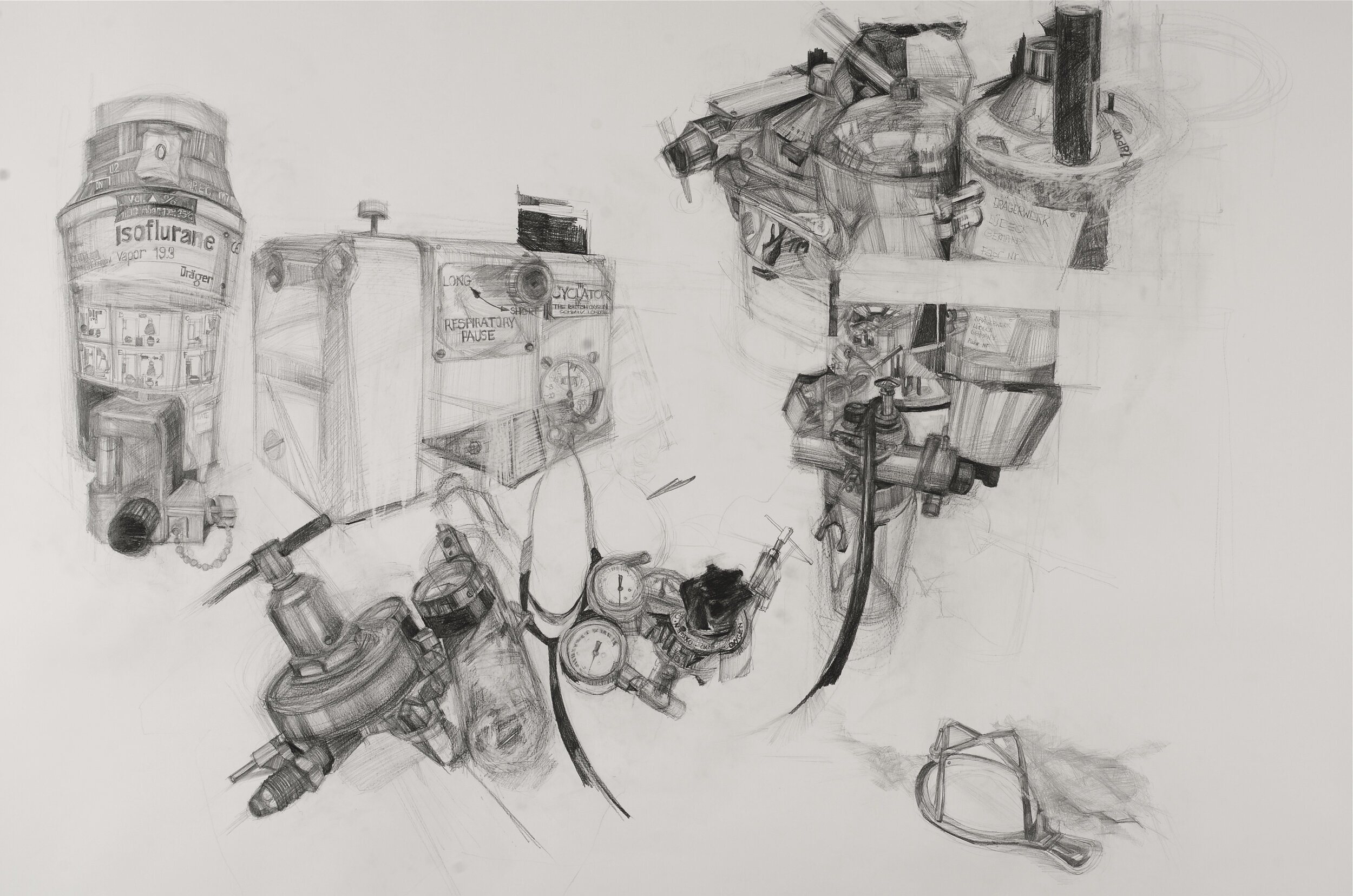

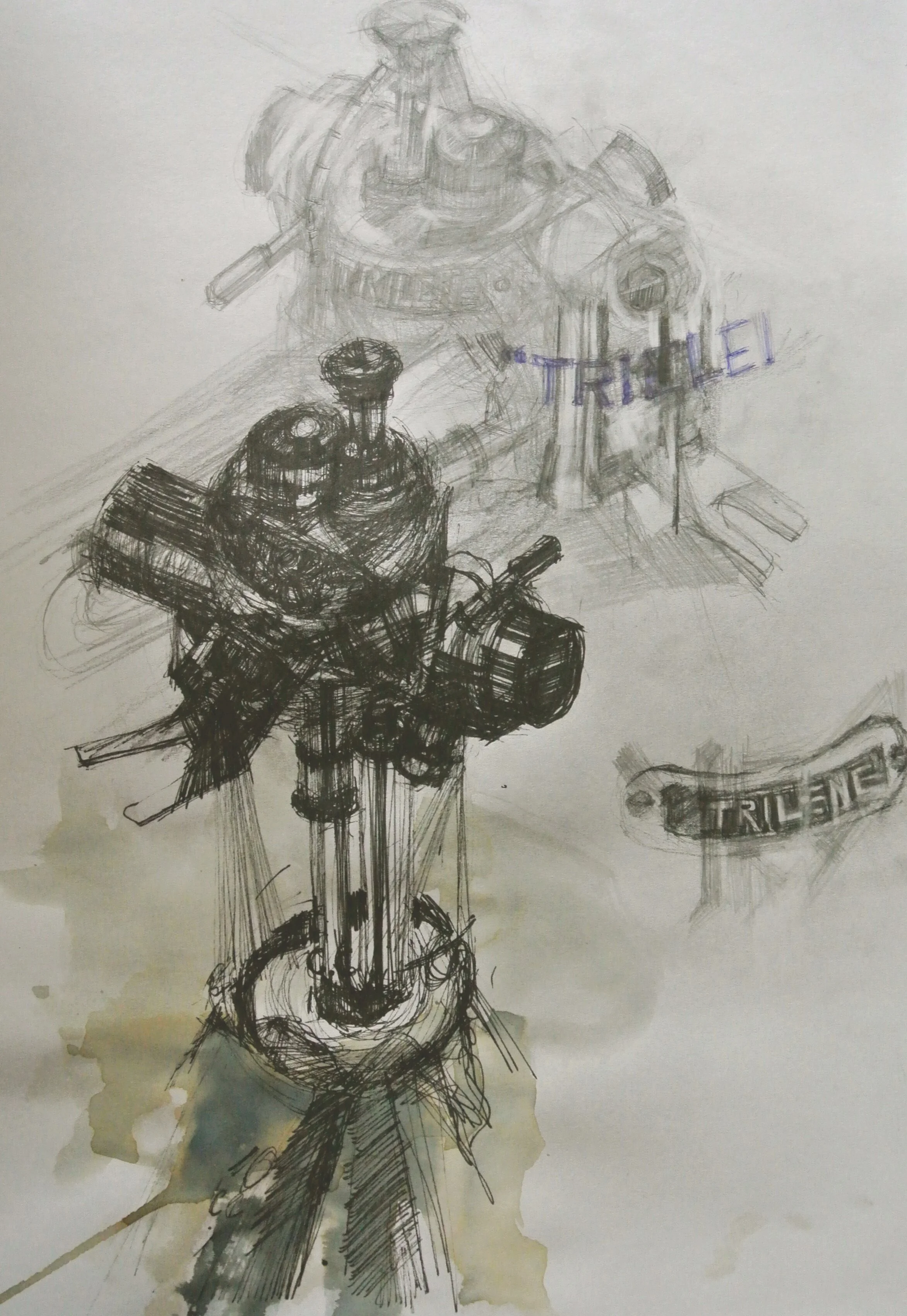

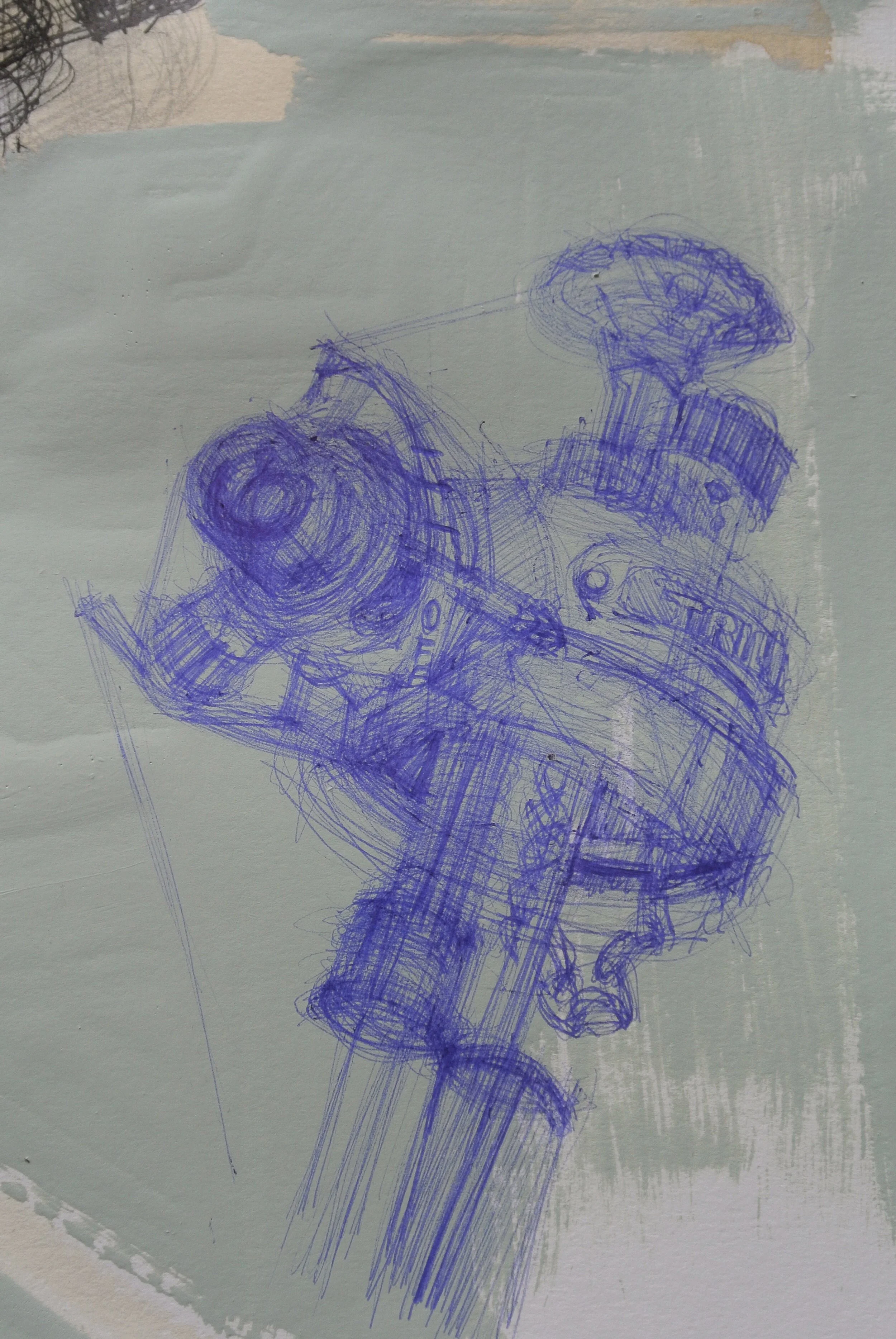

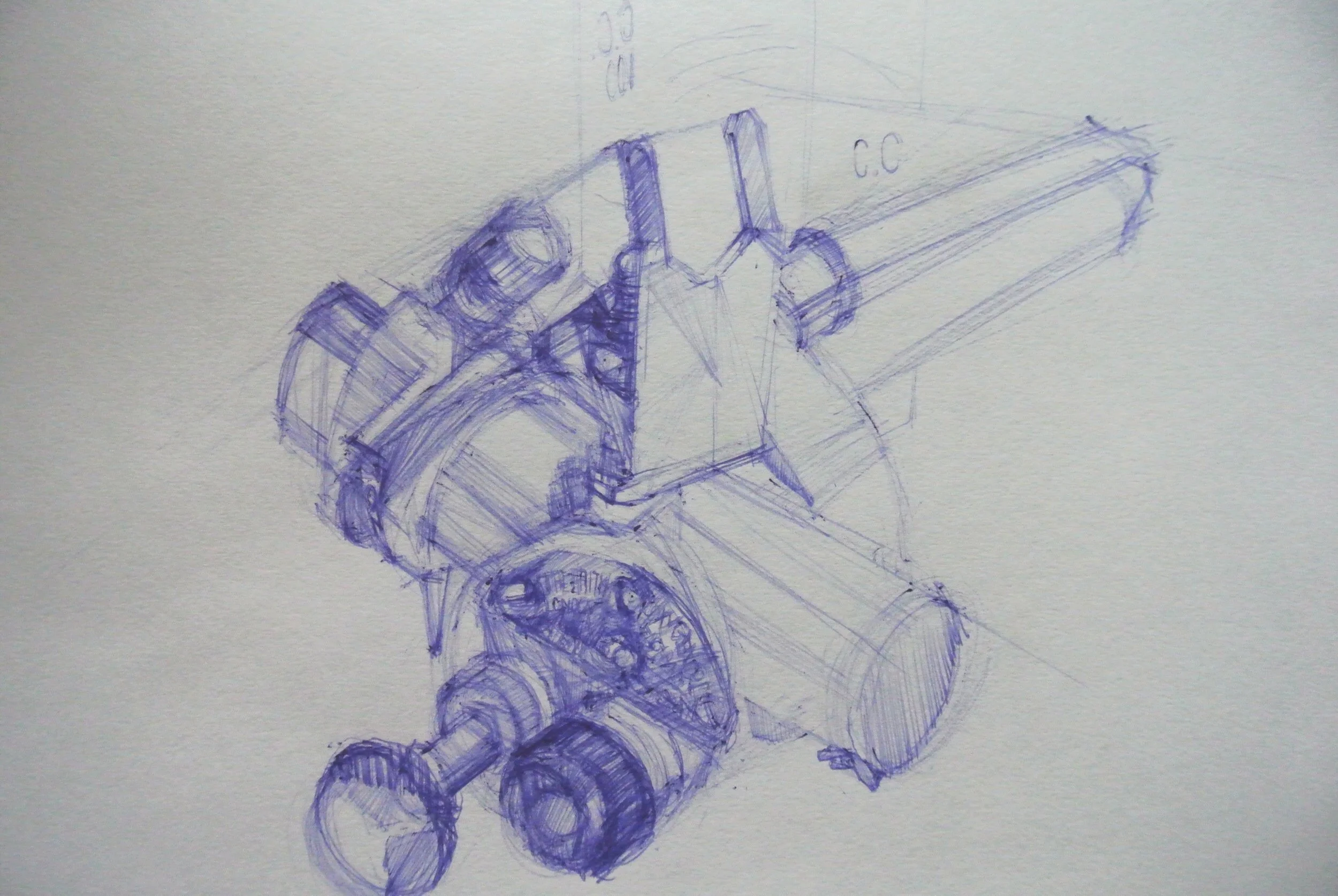

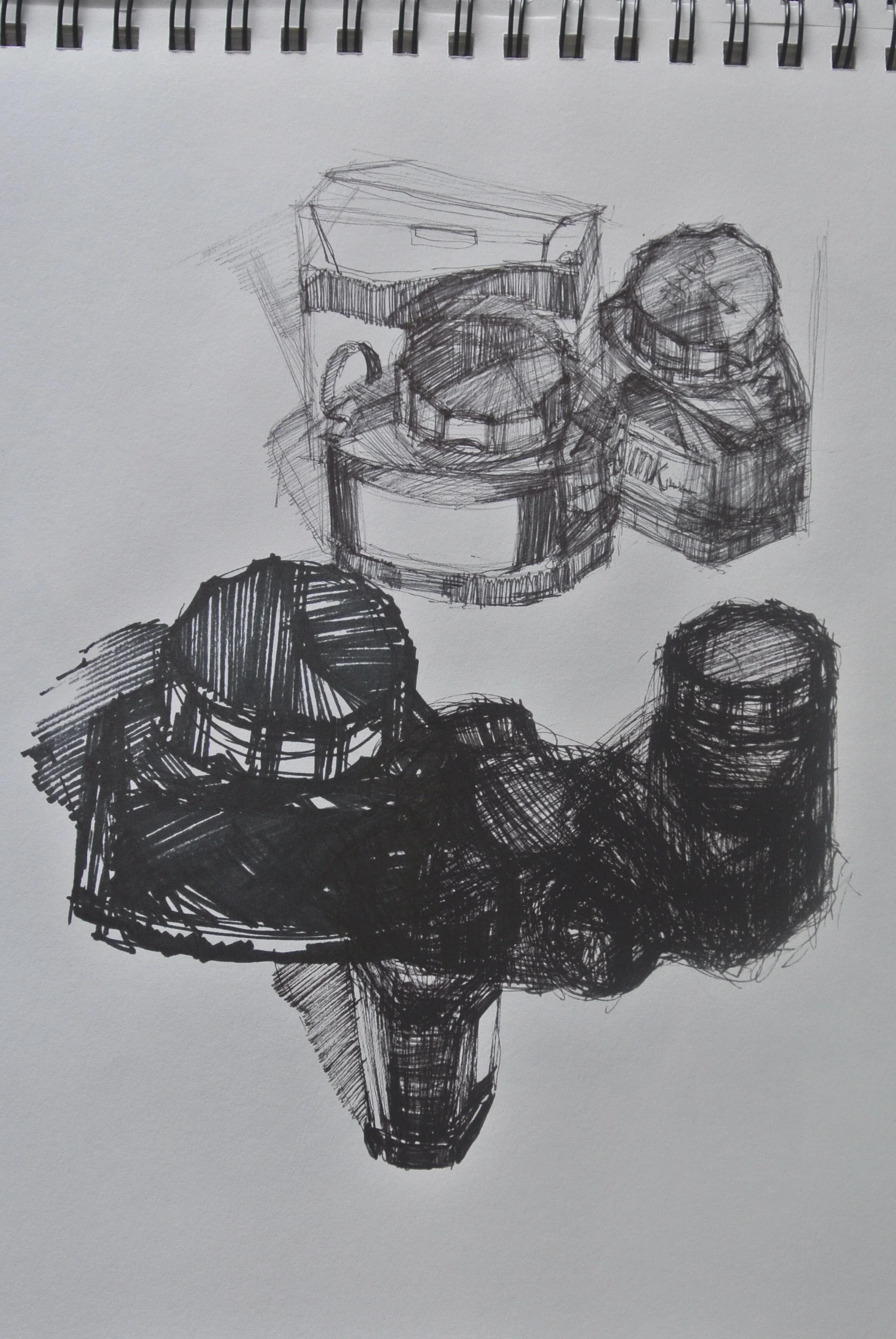

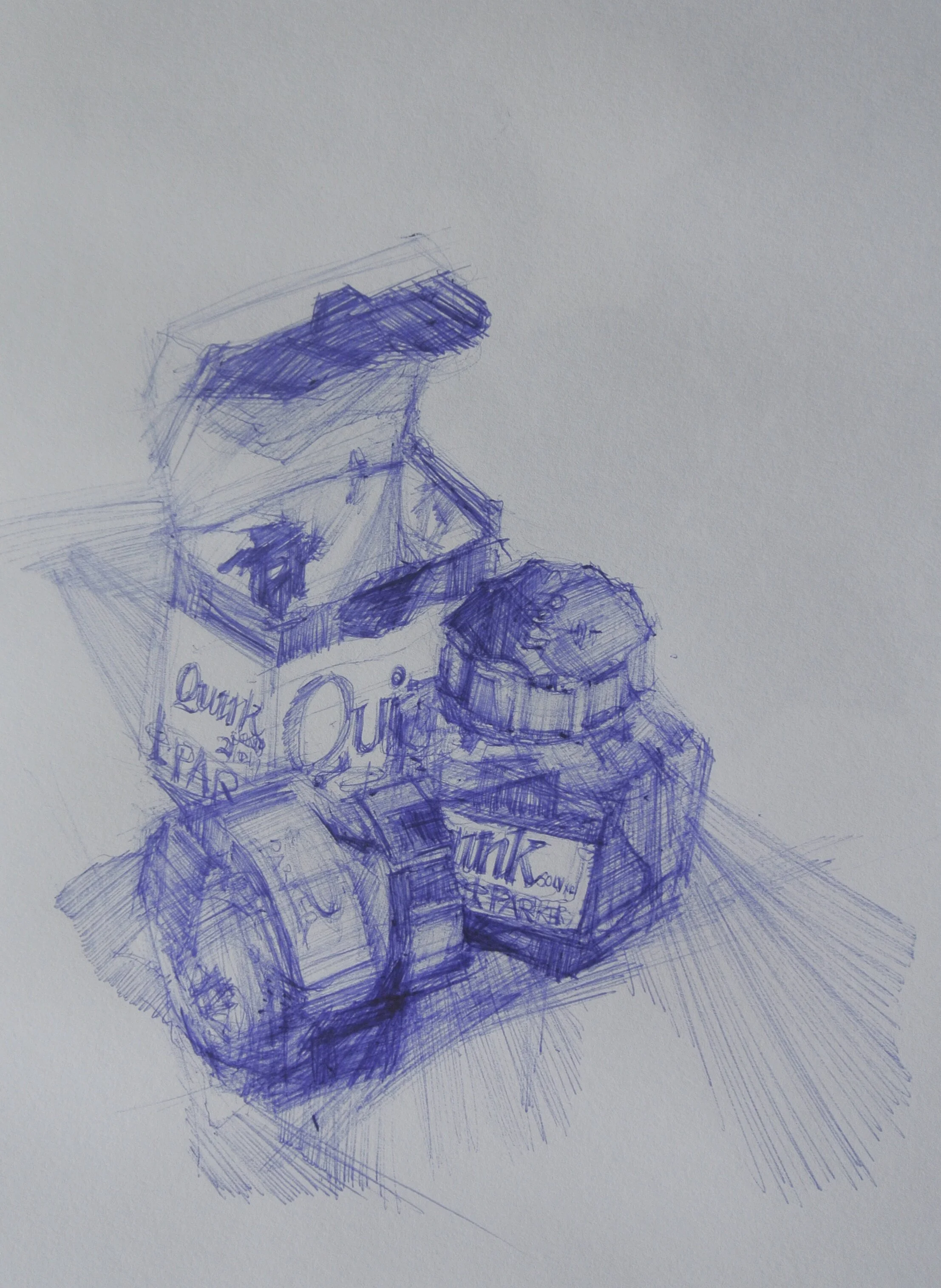

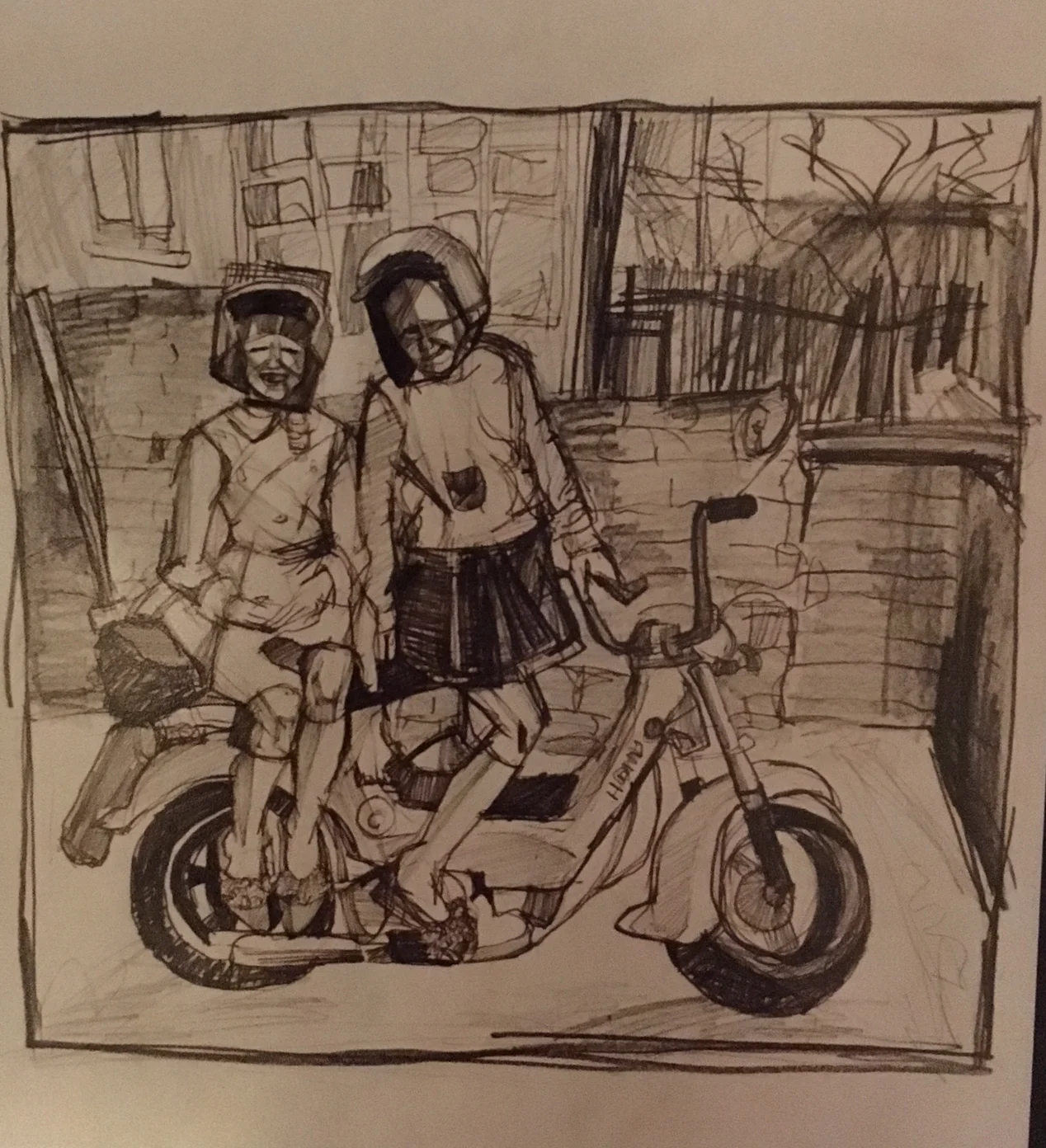

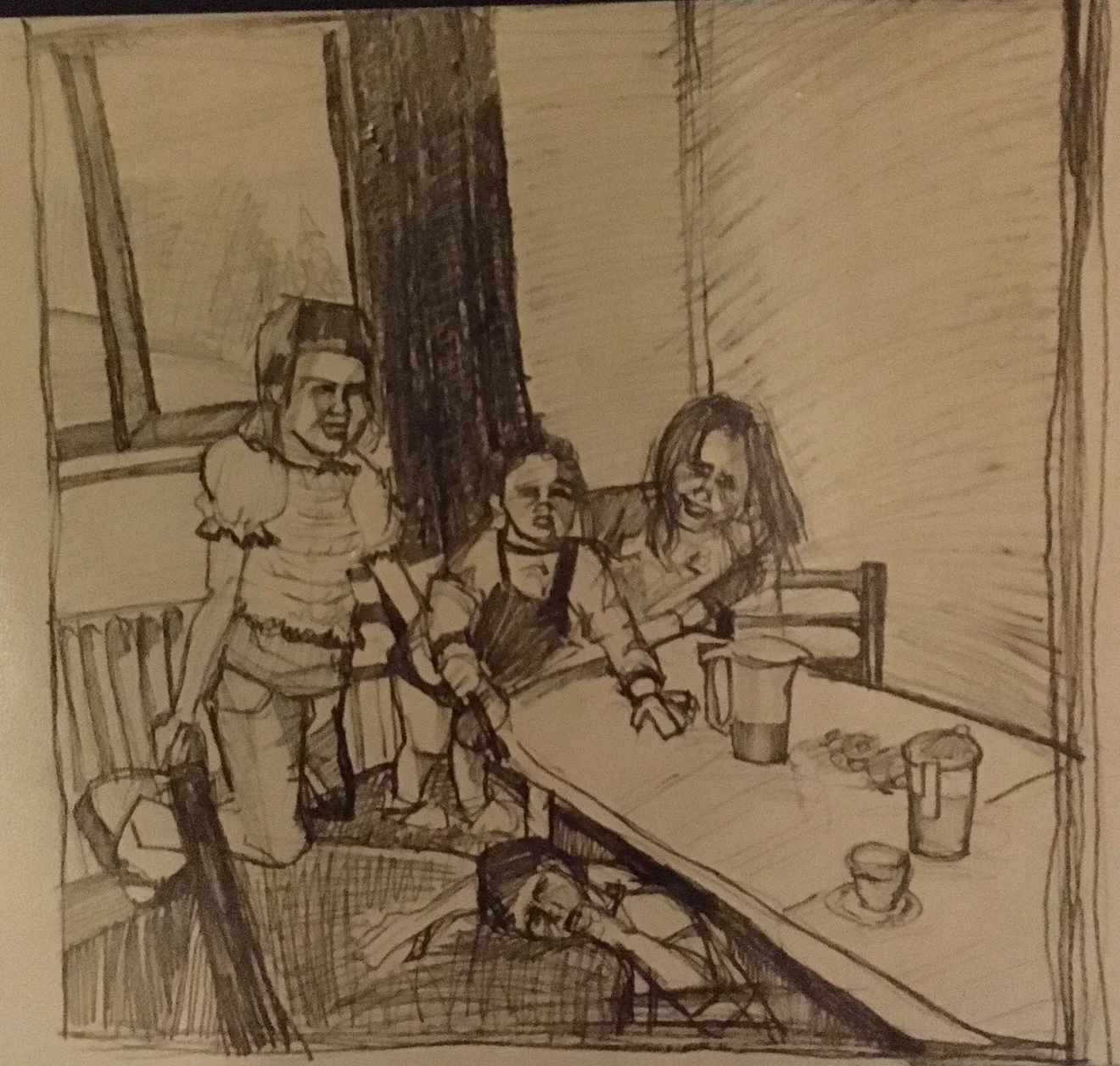

The work is particularly of note in Conway’s career to date as it is very much at odds with her medium of choice, representational through pencil or paint. In much like the way Morrissey wails about the state of the world, Conway’s wailing children represent her uncomfortableness with, as she states the ‘real or imagined pressure to conform to the current fashionable practice of utilising digital and multimedia imagery together with an academic writing practice in order to be relevant’. Conway speculated that these devices were becoming overused, formulaic, cliched and outdated as early as 2006.

In 2018 this begs several questions about how we engage with the digital in relation to art practice. In 2006, the use of digital imagery and installation work which utilise technology could have easily been brushed off as a crutch, although in today’s reality the use of work that utilises or refers to technology is for better or worse integral to our understanding of the self and how we orientate ourselves in a reality that is becoming increasingly interwoven with the online and a digital representation of that self.

The urgent feeling to do right and to concede when presented with these two screaming infants is a direct parallel with the artist’s attitude towards the screeching pace with which contemporary Irish Art scene is moving.

In totality the work suggests a weariness with the Irish Art scene during the time of the Celtic Tiger when technological advances were increasingly within reach of public hands and subsequently artist’s themselves. There is a feeling in this work of being awash with continual sensory overload at a time when representational work was starting to becoming dated in favour of video, digital photography and the interpretations of online and social media culture that would eventually succeed it and questions how we might retrace our path back towards the representational in 2018.

1. Berger John, 1972, Ways of Seeing, London, Penguin